The Beginning

Three, deceptively simple questions changed my teaching practice forever. These questions transformed my teaching from a deficit model to a growth model, that is, one that helps me clearly identify where my students are and push them further by having them do the hard work of thinking critically. The routine, called Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) involves students looking at an image and having a discussion led by the teacher using these three questions:

• What is going on in this image?

• What do you see that makes you say that?

• What more can we find?

I teach third grade in a Title One School in Spokane, Washington. In 2008, we began a partnership with the Museum of Arts & Culture and thus began my journey using VTS in the classroom. My first two years of learning VTS consisted of honing my facilitation skills, learning to stay true to the questions, and strengthening my ability to paraphrase my students’ comments. This was not an easy task for me as these new teaching strategies caused some discomfort and dissonance. I had to learn to hone my listening skills, build in time for unpredictability, and accept all points of view. As I became more confident, though, I was able to wean myself from manipulating the conversation toward my desired outcomes and to trust the process of VTS. This meant learning to let go of some of the control I was used to having, which was a difficult task in the “direct instruction” environment of traditional education.

In direct instruction, the idea is that as the teacher I have the all the answers, the “important” information comes from me, and my job is to make sure my students understand it. Learning VTS, however, taught me to think of my students’ needs first, to be comfortable with where they are, and where their learning is going. Students noticed that I valued what each child brought to the conversation. It allowed them to understand that knowledge is not “fixed,” that we acquire it through hard work, and that the more strategies we use to learn, the more capable we become as students. They began to be comfortable with the idea that learning is messy, takes time, and is never truly finished. Rather than focus on the product as being the sole proof of learning, my students and I discovered that the process itself is valuable and provides depth.

VTS created a culture of thinking in my classroom: as it became routine, students started to practice and use it throughout the day in all content areas. I began to speculate that using VTS as the core of my teaching in an organized, systematic way, while trusting the process, would deliver the same powerful outcomes in other areas of learning as the VTS discussions themselves did with art.

Three years later, in 2011-12, Philip Yenawine interviewed me for his book: Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. I was excited to see my work with VTS featured in several chapters and carefully read his “challenge” to teach writing using VTS.1 Would it be possible to create a structure for teaching writing with VTS? Could I shift teaching writing from assessment of learning to assessment for learning, as Rick Stiggins suggests?

For a variety of reasons, teaching writing is one of the most difficult tasks that teachers face. There is a wide gap of knowledge amongst students—and getting K-6 students to write with joy can be daunting. There are many skills and subskills demanded by the Common Core State Standards in areas such as writing forms, writing traits, grammar, and conventions. As a teacher, I had many questions about the instruction of writing: How can I teach all the targets? How can students demonstrate the standards for writing independently? How can I help students set goals and monitor them when each one has a different writing goal? I do not see myself as a rich, “polished” writer, or someone who knows the English language and its many rules extremely well, so how can I identify specific, granular gaps in students’ ability to write?

In pursuing answers to these questions, I understood that VTS would not survive as a stand-alone strategy in my classroom, with so many different curriculum demands placed on me. I needed to create a structure where VTS could be at the core of my teaching practice, with everything else radiating outward.

My quest to create and extend such a methodology began with the opportunity to collaborate with my VTS trainer, Heidi Arbogast from the Museum of Arts and Culture. Together, we spent five years developing, applying, and refining this method in my third grade classroom, eventually building from there to a district-wide professional development model called the VTS Writing Lab. At the core of both classroom learning and teacher-led learning is self-reflection. We found that students and teachers alike changed their behaviors when given time and a framework to self-reflect. The VTS Writing Lab provides this framework: it is a multi-layered, complex, rigorous learning environment for both student and teacher.

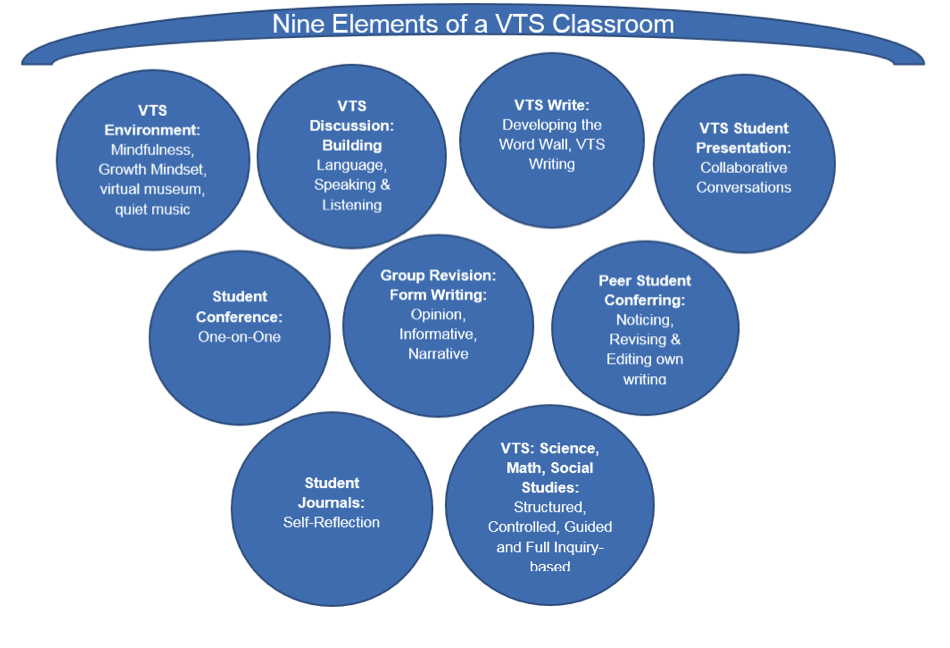

Through trial and error, we created what we refer to as the Nine Elements of a VTS Classroom, including the “VTS environment,” “VTS discussion,” and the “VTS Write.” These elements organize and “layer” the tenets of VTS throughout each content area, beginning with writing.

I use this structure in my third grade classroom as well as training labs for fellow teachers. Below, I will share our definitions for some of the key elements of a VTS Classroom.

One: The VTS Environment

Creating a VTS environment in the classroom involves mindfulness of the core concepts of VTS: keeping an open mind, listening to all points of view, valuing a diversity of ideas, meeting each student where they are as a learner, and fostering a growth mind-set for both teacher and student. We found that VTS works well in tandem with a wide range of teaching strategies, from classroom meetings to mindfulness practices.

The environment of VTS allows students to understand that all ideas and points of view are valued. They begin to speak their minds without any hesitation because they know there will be no admonishment from their teacher. Once my students understood that this was their learning environment, they began to relax in a way that they could not when I was using other methodologies. They came to the discussion with their brains not in a “fight or flight” mode, but ready to engage in a more relaxed mode of thinking.

After becoming skilled using this strategy with art, my students were able to transfer this culture of thinking into other contexts, creating a supportive, caring, thoughtful environment for themselves and each other.

Two: The VTS Discussion

Facilitating VTS discussions with art images is the key building block in constructing the VTS classroom. It allows me to understand how my students think as well as what they already know. It is very important to begin this process by discussing art images to promote a risk-free, inquiry-based classroom.

My students noticed that I valued what each child brought to the conversation and they observed that as I linked, named, framed, and clarified their ideas, lifting the language for all in the classroom, this caused everyone to think more deeply. In addition to building language and listening skills, it allowed me to identify and assess what every student was thinking, as well as their use of Standard English. I can identify their learning gaps and take steps to help students in the moment.

Before the discussion, I like to brainstorm new vocabulary about the art image, in order to help prepare me to add vocabulary during the students’ discussion. Keeping the discussion student focused by remaining open to their ideas, linking, naming, noticing, paraphrasing, and scaffolding their thinking are complex skills that require active listening from the facilitator. This takes time and effort but is the key to developing a VTS centered classroom.

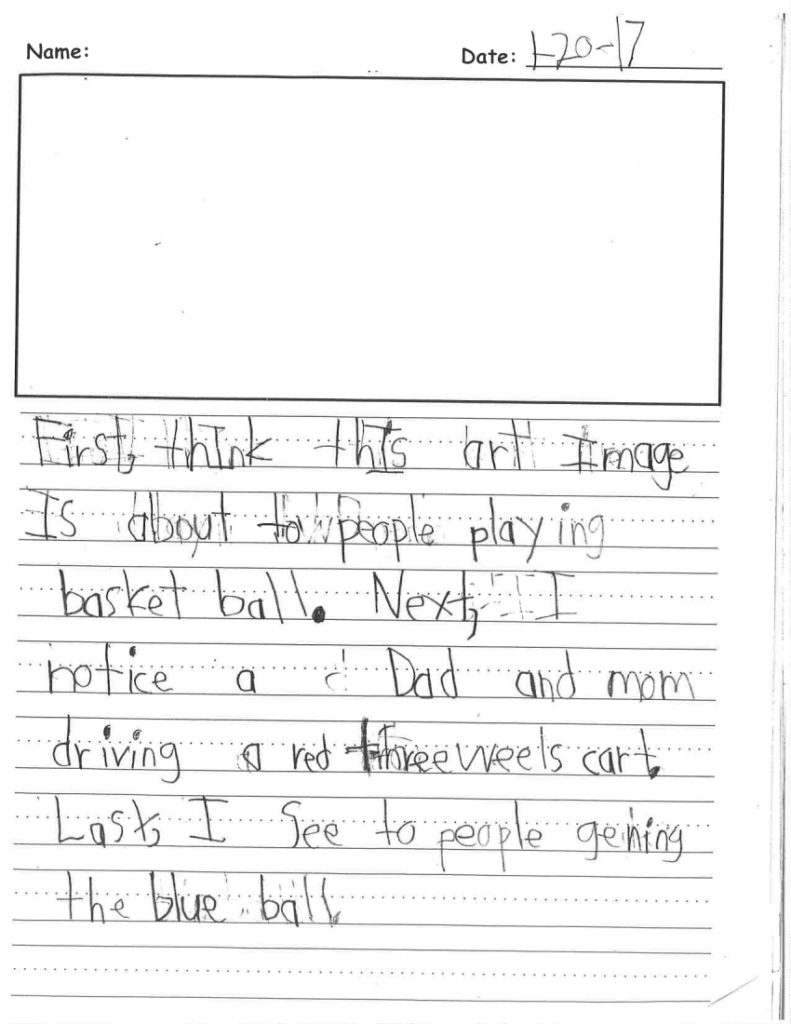

Three: The VTS Write

We capitalize on these discussion skills by having students write after every art image and discussion. During this time, I ask reflective questions: What is going on with my students? What do I see that makes me notice this? What more can I find? With Heidi, I also began to build a writing framework that is both highly structured and guided by the needs of the students (not necessarily the “time order” of the mandated curriculum). Our writing workshop began to take shape using the same three VTS questions centered on student writing samples. The basic framework has two phases:

Phase 1: VTS Discussion and Independent Writing Time

• Facilitate a VTS Image Discussion

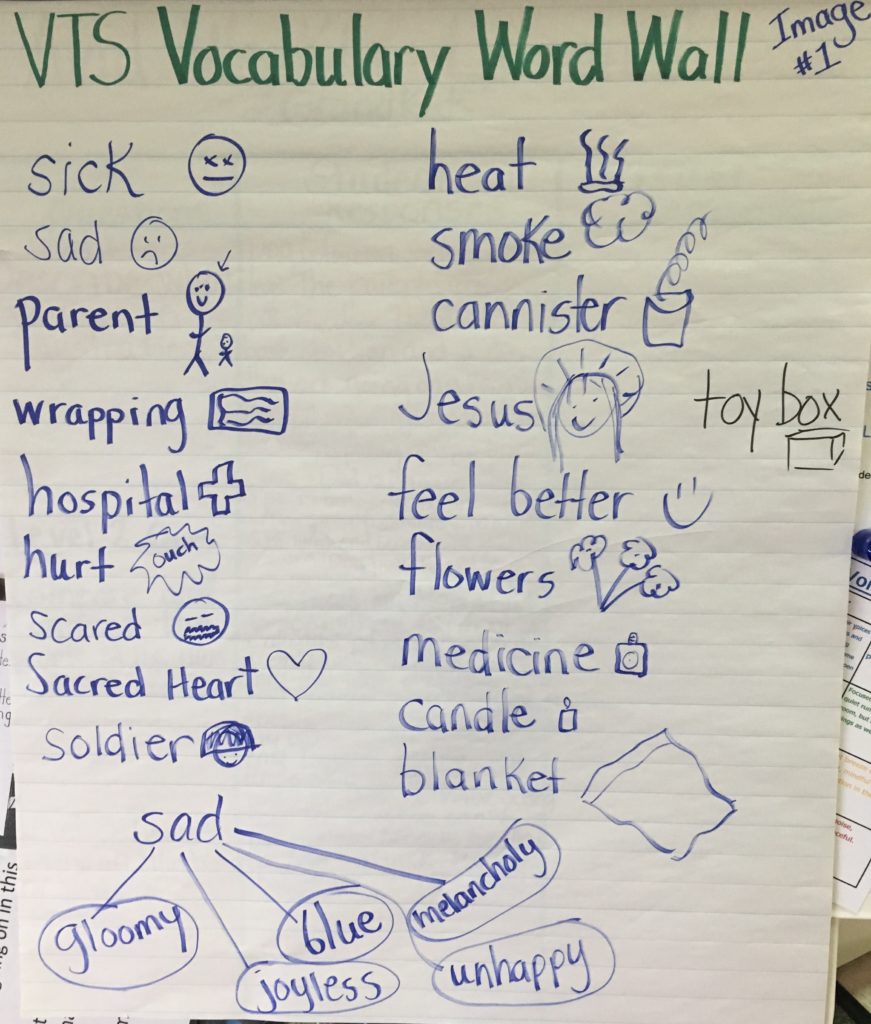

• Develop the VTS Vocabulary Word Wall (generated by the students after the discussion)

• Students write independently for twenty minutes, building on the VTS discussion

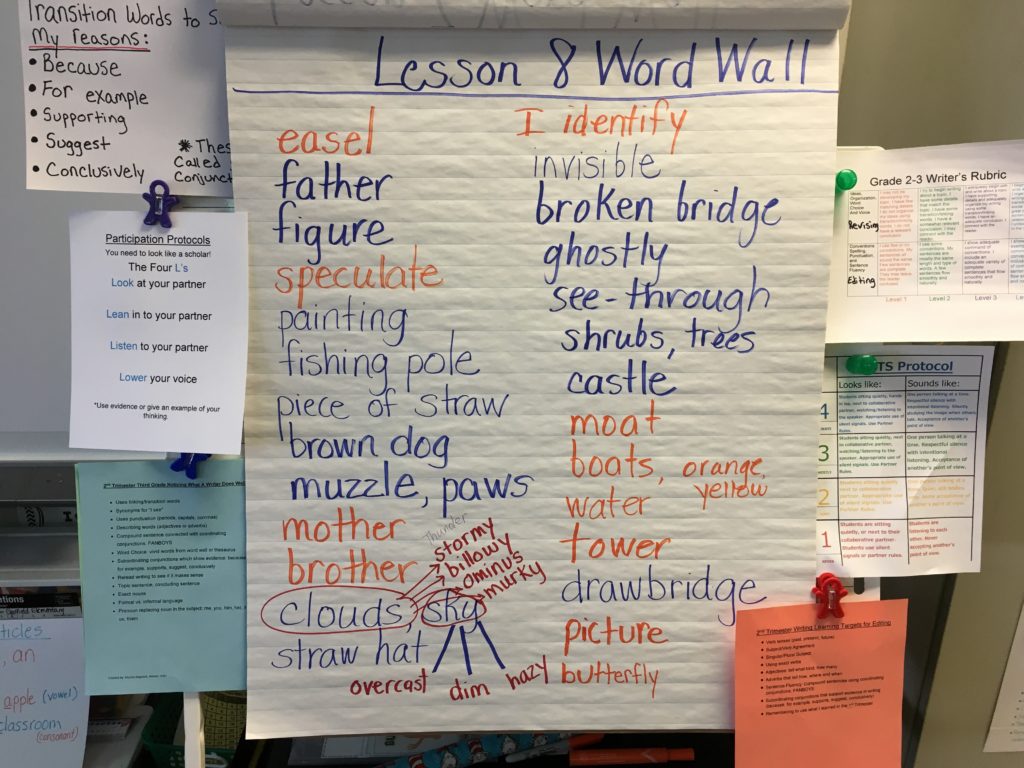

VTS Vocabulary Word Wall

I develop the VTS Vocabulary Word Wall immediately after the image discussion. The students generate this list, which immediately makes them feel they are part of the writing process. Everyone wants to participate because the words the third graders hear in the discussion become the word wall, which allows everyone the opportunity to use them in their independent writing.

For emergent writers, I also draw a quick sketch next to each word. This way, students have fair and direct access to meaningful words that they create as a group. The word walls vary according to the purpose. I can extend their vocabulary by choosing several words to find as synonyms, or I can group the words into nouns, verbs, and adjectives (hitting our grammar standards), or into character, setting, and detail (teaching our reading standards). In this context, vocabulary is purposeful, has meaning, and reflects the words spoken in the image discussion. This supports students in writing their ideas independently for twenty minutes.

I post an anchor chart listing the traits of good writing for all to see and use as they are independently writing to help scaffold their learning. They can also access several other anchor charts posted around the room, listing things such as transition words, directional words, and synonyms for “I see.”

A word wall, including word bonds developed using a thesaurus, surrounded by anchor charts students use while they are writing

Phase 2: Group Revision Process

• Analyze the students’ writing to identify the optimal learning targets that will benefit the whole class

• Choose one student’s piece of writing

• Display the selected writing to the students and facilitate peer-group noticing lessons and revising and editing lessons

Peer-group noticing lessons

The peer-group noticing lessons have the same format as the VTS discussion itself. I ask:

• What do you notice the writer did well?

• What do you see that makes you say that?

• What more can you find?

• Why is this important?

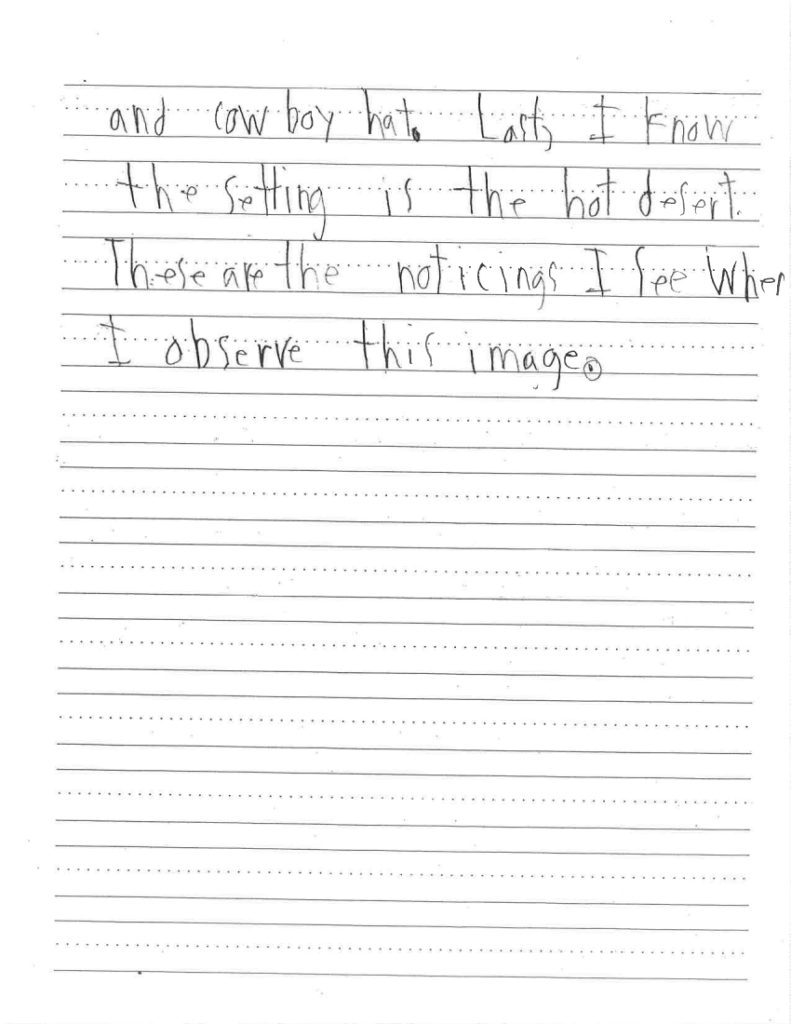

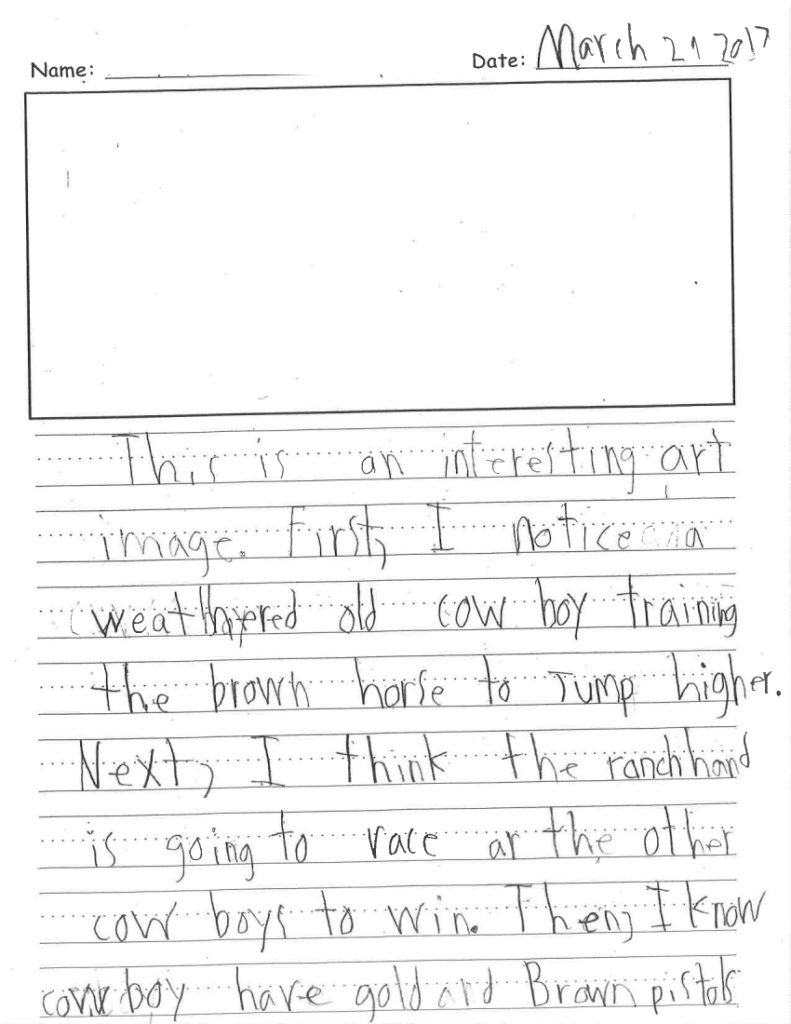

The students focus on writing traits (ideas, organization, word choice, and voice), grammar skills, and conventions (punctuation, spelling, sentence fluency) as well as the academic vocabulary that they need to learn to become proficient writers. The fact that they learn it through each other’s writing and thinking adds relevancy as well as motivation.

The peer-group noticing lesson allows students to dip back into the image, to listen to and observe what a student writing sample looks like, as well as learn how to think, collaborate, and share their ideas together in a group. They ground their thinking by providing evidence about the noticing they find. And because students notice only what the writer did well during the noticing lesson, it becomes a focal point and celebration around what the whole class does well as writers. They are able to understand the message of “focus on what you can do well and then grow from there.”2

Another critical step in the noticing lesson is for me to share the “learning histories” with my students so they can recognize how far they have come in their learning compared to the beginning of the year. I continually connect where they have come from to what they know and can do now. They learn to understand that writing is messy and that it is a process. They continually grow as writers in a living, breathing, writing community. This format allows them to become a cohesive, thoughtful, authentic group that cares for their writing throughout the year. They learn to continually set individual writing goals that have personal meaning and hold each other accountable for meeting those goals.

In valuing their own writing by putting it up (anonymously) for all to see and grow from, writing becomes purposeful for them. They begin to build stamina as writers and to see writing as an act of joyful learning.

Revising and editing lessons

The revising and editing lessons focus on a writing/grammar learning target by showing an example of student writing to revise or edit. Using the same selected piece of writing, students analyze a sentence or two from the text. The questions I use for these lessons are:

• What can you add or change to the writing below?

• What do you see that makes you say that?

• What more can you find?

Students examine the writing again; the questions ask them to provide evidence for their thinking. The third question makes it clear to students that we may have more than one kind of thinking out there and that all thoughts are valued. Revising becomes a more open-ended process, but students also understand the goal of revision. They learn that we revise to make our writing more clear and precise.

In all of these VTS Writing Lab components, students are doing the hard work: they are answering the questions; they are providing the evidence; and they are accountable for their own learning. After group lessons, they analyze their own writing using student reflection handouts that have the same VTS questions. With their partners, they help each other analyze their own writing and set their next writing goal.

Self-reflection is then followed by peer-reflection: they read their own work to a group of four, share their self-reflection handouts and their own personal goal based on the CCSS writing goals. The group of four looks at each individual goal and calibrates the goal to match the writing.

In other words, they hold each other accountable for their writing goals. They ask each other:

• Is the goal valid?

• What do you see that makes you say that?

• What more can we find?

VTS reflects our writing culture. This methodology makes the writing process doable and realistic for students. Our beliefs, which VTS supports, are:

• Students come to us as writers. Oral retelling and drawings are a child’s first form of writing. The VTS discussion supports this in a risk-free setting.

• Writing is social. Writing happens in a community and is collaborative. Ideally, it builds on peer interaction. The VTS discussion gives the students a needed framework for their follow-up writing.

• Writing is a process. We start where students are and build from there. We pre-write, write, share, revise, and write again. Process is as important as product. The writing lab allows students to self-reflect and set their own writing goals.

• Writing is developmental. Children start with language, scribbles, drawing, inventive spelling and move to standard writing. VTS writing supports and honors each child’s writing stage.

• Writing connects to reading. When we “read” the VTS image, we make meaning in conversation. The same elements that are in our writing are in reading: setting, characters, narrative, information, and opinion.

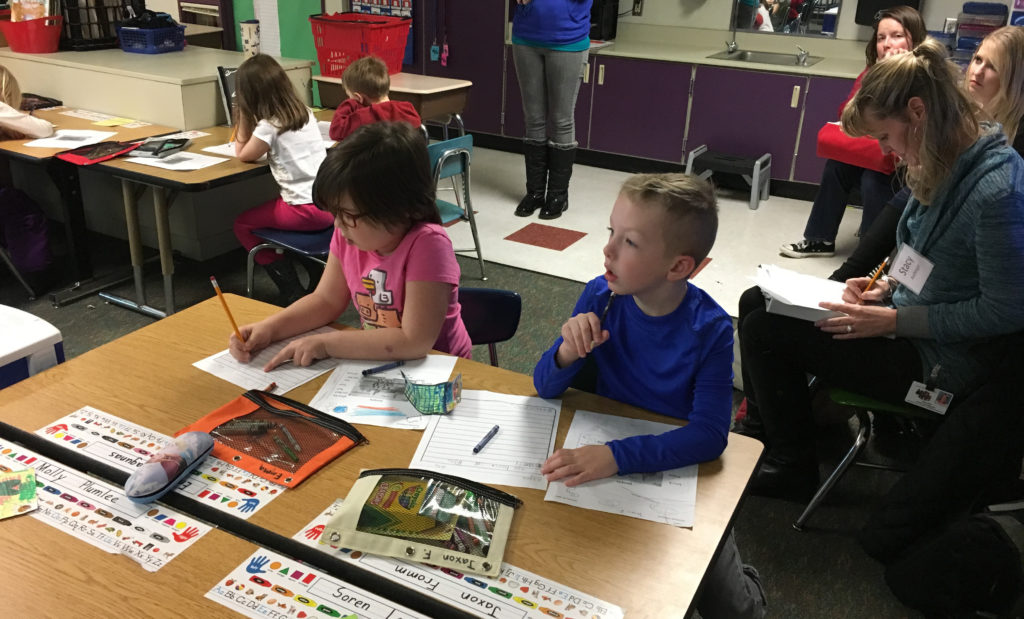

Four: District-Wide Professional Development: The VTS Teaching Lab

Just as VTS is student centered, the Teaching Lab is teacher created. Many teachers struggle with the same questions I have about teaching writing, we often do not have time to collaborate with peers and reflect on our writing instruction so that we can continue to learn and grow from the process. In the teaching lab, we focus on creating a supportive, conducive environment to allow a culture of thinking in our classrooms.

Teachers in the teaching lab are able to observe each other so that we can build our skills over time utilizing a process of a pre-brief, observation, de-brief, self- and peer reflection. No one lesson we observe is perfect, but we “muddle” through together and the time we spend in these labs is very powerful. Through this process, teachers find themselves transforming their own mindsets and beliefs about how students learn. They, too, change the way they think about the classroom environment, moving from a “fixed mindset” to a “growth mindset.”3

Through teacher feedback, we have heard that this teaching and learning is reflective, deep, and lasting. I believe this is because the lab model emphasizes constant reflection, building the skills of facilitation and precise content knowledge. These include deepening the linking, naming, framing, scaffolding, and paraphrasing skills for the VTS discussion as well as the writing content areas.

Conclusion

With VTS at the core of our practice, we can more skillfully move to an inquiry-based model for all teachers. We understand the importance of creating a culture of thinking using VTS, which we can then transfer into all content areas for more effective learning. Inquiry-based learning may be the new “buzzword” in education, but it is at risk of failing to fulfill its promise if we do not use a strategic methodology to implement it. VTS helps unpack the process by supporting teachers and students in their journey of inquiry. Facilitating cycles of inquiry with students provides the support they need to close the gaps in their learning and understanding.

At the heart of our practice, teachers are concerned with making a difference and reaching every child. Because of the VTS Teaching Lab, teachers in my district are embracing VTS as a way to do this with compassion and meaning. We are working collaboratively to create real change within our schools. The journey continues with all the stakeholders—administration, teachers, students, art educators, and grantors4—on board, a journey that began with learning to use three, deceptively simple questions.

Questions or comments? Contact us.

Footnotes

- 1 - Philip Yenawine, Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Education Press, 2013), 98-99.

- 2 - Their writing also provides me a window into their thinking. This way, I discover the importance of being a skilled facilitator during the VTS discussion. I can directly see how my linking, framing, scaffolding, and paraphrasing supports the richness of their writing. Their writing informs my next steps in teaching.

- 3 - Carol S. Dweck, Mindset: the New Psychology of Success (New York: Ballantine Books, 2008).

- 4 - The VTS Teacher Lab was developed with support from NEA and Ellison Foundation.