Through my experience facilitating VTS, I’ve built my work around the central question: how to learn? Learning requires collaboration and a humble reorientation to knowledge that encourages improvisation. In other words, learning to learn.

Learning to learn. This became a practice that began with deep listening. I realized that much of how I make my work now is predicated on my past as a VTS facilitator. After six years facilitating VTS discussions and coaching public school teachers in their classrooms, I have taken its values with me, and continue to apply them in my work as an artist and in my personal life. The practice of VTS is where I first learned how to actively listen, and how listening relies on trust. For instance, accurately paraphrasing a student’s comment not only helps me understand what they are seeing, but it honors their ideas in a way that encourages them to trust learning—and more importantly, to trust themselves—and that the learning process is both individual to them, and dependent on the group.

In a country whose public education system is deeply threatened and whose first amendment rights justifies the freedom to speak, I often think about who is listening, who gets to listen, and which listeners are valued. In school, being able to verbally articulate one’s ideas is more valued than one’s ability to listen. Speaking is seen as active and listening, passive. Yet garnering the ability to listen thoughtfully can be incredibly empowering; it trains the heart to act and makes space for those who cannot or choose not to speak—the quiet, the shy, even the hyperactive—and can extend into seeing structural limitations within someone’s learning process. And in that awareness, there is the hope to change, to reassemble various learning processes and rearrange how knowledges can be produced and shared.

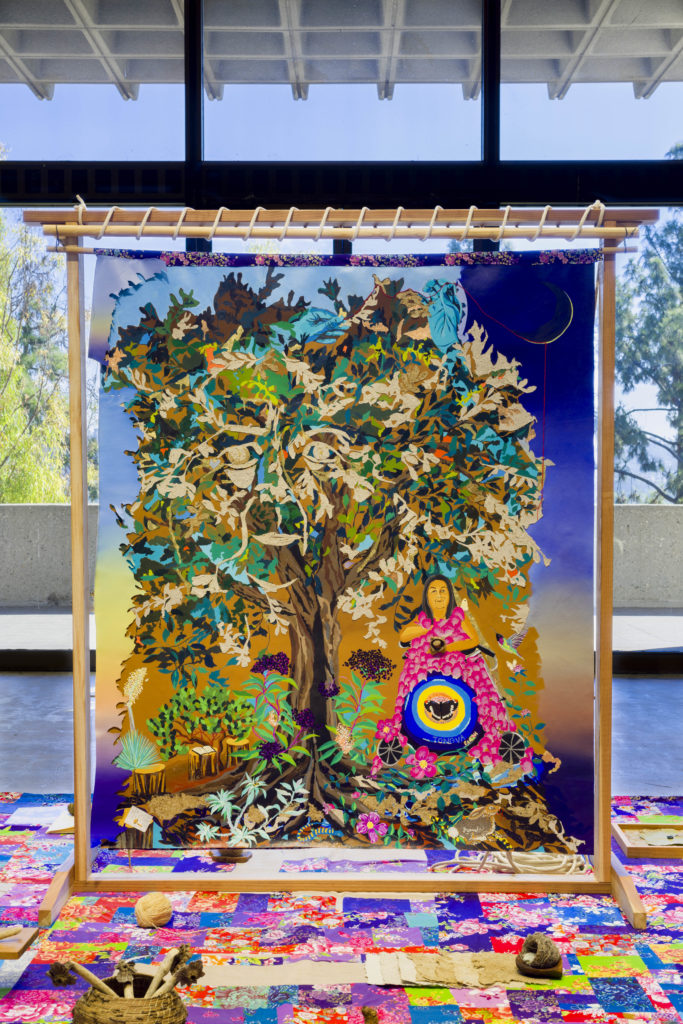

iris yirei hu, Lessons from Wise Woman (Tongva Elder Julia Bogany), Grandmother Oak Tree, and Hands, 2018 (deatail). Photo by Ruben Diaz.

Learning to listen made me more careful. My work as an artist allows me to tune into the histories of a place that were erased, made invisible, and forgotten. What about those that have been historically and systemically silenced, whose articulation may not depend on visibility, scale, or fluency by standards established by the ruling class? How does one make sense of their own participation in the world, taking into consideration pasts that have formed legacies of colonialism, disenfranchisement, and trauma? For me, resolution or reconciliation is not the destination; rather, the nebulous arrival presents itself differently each time in a constantly unfolding journey of learning, collaboration, and rearranging our relationships to power.

The three questions of VTS yield a multiplicity of responses, which allow for more freedom and diverse possibilities for discussion, yet they serve to ground conversations. A skilled facilitator allows a conversation to build, with its harmony, riffs, dissent, and dissonance, while being open to receiving insights. In a VTS discussion, divergence is what makes a conversation fruitful. Applying that concept to my work, I think that solidarity also requires divergence, a shape-shifting refusal to consent to the status quo.

As an artist, I have been learning about the uses of plants, with a particular attention to their dye and medicinal applications. In December 2017, I travelled to Teotitlán del Valle in Oaxaca, Mexico to learn Zapotec weaving and natural dyes. There, my teachers Juana and Porfirio Gutiérrez told me that plants are shy and jealous. Knowing this, the most fascinating part about working with plants is that they do not conform. Because you use the same amount of indigo and fructose each time does not mean that indigo will ferment in the way you expect. The same amount of pomelo juice to acidify the cochineal does not necessarily mean it will yield the bright red that was once so highly coveted by the Spanish. Plants are very much their own, and will show you their true colors once they have developed trust in you, meaning, on their own terms.

I developed this inclination towards plants when I began to understand the power of listening—a careful practice that encompasses observation, smell, taste, feeling, and curiosity. How do I listen? I begin by being open and present. I value the significance of the encounter, and the collaborative improvisation that arises when two or more forces meet. I like surprises and discoveries, and that also means working through dissent and conflict.

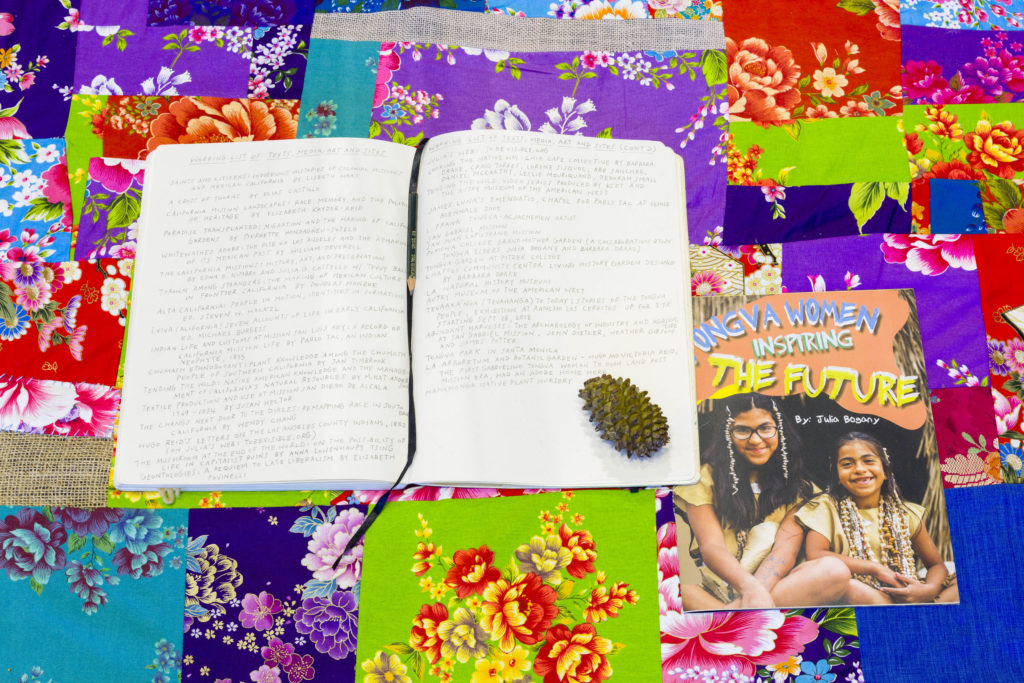

iris yirei hu, Lessons from Wise Woman (Tongva Elder Julia Bogany), Grandmother Oak Tree, and Hands, 2018. Assemblage with acrylic and oil paint, handmade oak leaf and yucca fiber paper, gold and copper leaf, embroidery, needle, collage, burlap, hemp and cotton string, Navajo loom, cotton rope, earth and pressed grape leaf from San Gabriel Mission, figeater beetle corpse, ash, incense, hand carved soapstone bears, handmade pine needle baskets, natural dyed indigo and beige Churro wool, fallen Scott’s oriole nest, fallen robin’s nest, hand carved oak, manzanita, and pine pieces by David Bell, glass frame, rocks, yucca stalk, dried agapanthus flower, Ziploc bag, canning jar, mahogany pedestals, printed matter, drawings, handmade quilt from Taiwanese Hakka floral textiles. Guided by Tongva elders Julia Bogany and Barbara Drake; Los Angeles Natural History Museum Collection Managers Chris Coleman, Kim Walters, and KT Hajeian; Professor of History at Cerritos College John Macias; and independent reading. Photo by Ruben Diaz.

In my most recent piece, entitled Lessons from Wise Woman (Tongva Elder Julia Bogany), Grandmother Oak Tree, and Hands (2018), I went back into my hometown of San Gabriel, California, where I have been working with elder Julia Bogany for the past few months. The Tongva are native to the Los Angeles basin. I have been meeting her to learn about Tongva history, soapstone carving and pine needle basketry, uses of plants, her family, and her great granddaughters. The work began with my evolving relationship to landscape, particularly the histories and manifestations that have thrived and continue to thrive, but are not immediately visible to me. This work was a revision of my own institutionalized learning experience, particularly regarding the legacy of California’s indigenous—not only people, but also plants, animals, earth, ways, and of the land upon which we walk.

Following the Taiwanese immigration wave of the 1970s, my grandparents bought a home in San Gabriel, the site of the fourth Spanish Mission in California, where thousands of Tongva, as well as Tataviam and Chumash, were enslaved and renamed Gabrielino. My grandparents’ idea of home ownership and property in California took into consideration their own displacement following two wars, but did not consider the troubled history of the land upon which they settled. Now, San Gabriel mostly consists of Asian and Latinx residents. I have been working with Tongva elders to deepen my engagement with the land upon which I grew into being, and have been learning the importance of honoring the indigenous. By studying landscape and the interdependency of human and non-human living beings, my work aims to cultivate a multilayered proposal of collaborative survival. One that decenters fixed notions of erasure and survival in relation to indigeneity and immigration, and does so by centering and honoring transformative, resistant, and active futurities.

iris yirei hu, Lessons from Wise Woman (Tongva Elder Julia Bogany), Grandmother Oak Tree, and Hands, 2018 (detail). Photo by Ruben Diaz.

Tending a garden requires care. Within the last year, my partner and I have collected different kinds of agave and cacti from freeway underpasses, traffic islands, and parking lots. Underneath each agave, babies sprout from the ground, which gardeners are instructed to remove for decorative reasons. Managers like pristine, tidy, and manicured settings, so the babies are sacrificed and thrown out. We pick them and watch them grow. We have a lot of life in our garden; our garden is a rearrangement of landscape as we experience it. Each day reminds me of the fact that they already don’t require much water, and we facilitate their growth by being slow, present, and intentional.