VTS can be used to help build conversations with people with dementia.

Nancy was always impeccably dressed when I visited her. She typically had on a blouse layered with a flowered sweater, carefully ironed pants, and pearls. She is living with Alzheimer’s, a form of dementia. Nancy resides in a specialized memory care unit at a facility in Massachusetts. She attended every monthly workshop I presented, but rarely participated during the actual art-making time (we used watercolors or sometimes made a collage, for example) other than calling out strings of comments such as “What are we doing here?! What is this?! I’m not doing this!”

These intermittent remarks would continue until the Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) portion of the workshop. I set a laminated image of Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting (1666–1668) before her. “That’s okay,” I would calmly and cheerfully reply, “I’m just going to leave this here for now, you don’t have to do a thing.” Within minutes, Nancy engaged in our discussion.

There are some things inherently built into a VTS session that sync beautifully when working with adults with dementia. These adults need more processing time, up to a minute or so, after a question is asked. VTS teaches us to honor that quiet, letting the question What more can we find? simmer while the viewer is looking closely and thinking.

“There’s a cat!” she said, pointing to the feathery crown of pale blue on a figure’s head. “You see something that might be an animal,” I replied, “What do you see that makes you say that?” “Well just look at it!” she replied. “You can see the fur.” Within minutes I learned that Nancy had a cat and soon several people in my small group of eight were telling me about their pets. We all rejoiced in our knowledge and experience with cats and pet memories, but no feelings were hurt when someone soon suggested that this might not actually be a cat, because we could all relate to that feeling of ‘softness’ in the painting that reminded us of cats.

VTS helps us connect with art.

I was first exposed to Visual Thinking Strategies at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. At that time, I was teaching art at an elementary school and had received a multi-visit grant, which allowed me to choose a class to bring for three visits during the school year. I picked a lively group of fourth graders, notable for their seemingly constant and ‘not on topic’ chatter. But their excitement in class was contagious.

We were standing before the monumental painting, Tea Production in China (c.1790-1820) when I noticed something extraordinary happening. The students were talking about the art! To say that I was stunned is an understatement. Listening to them ask questions, hearing how they responded thoughtfully and how they listened to each other, I was incredibly proud of them. I had never seen my students so focused or intimately engaged with a work of art. I knew then that I wanted to learn more about how to use this technique in my classroom. I wanted every student to have this opportunity and to be part of these kinds of discussions.

Beyond the Classroom

I received my initial training in Visual Thinking Strategies at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where I was on the Education Advisory Board. At that point I bought Philip Yenawine’s book and watched every VTS video I could find. After my training, I began facilitating weekly VTS discussions in my classroom.

Three years ago, ready for a change, I left public education and started my own business providing Visual Arts Workshops to seniors in residential settings. My work with memory loss came about quite naturally.

I have personally witnessed the long, slow, goodbye of Alzheimer’s. My funny, gentle father-in-law was the first close relative to be diagnosed (there has since been an uncle who died a few years ago… and now an aunt). Papa, as we called him, developed Alzheimer’s in his early sixties, many years ago, before we had the education and resources of today.

Back then, I had no idea what to say to him. I found myself staying away, only rarely visiting. This kind of semi-estrangement can happen as the disease progresses. The experience of sitting with someone who no longer knew who I was—someone I had such a strong and loving relationship with, so many shared laughs over our ridiculously competitive games of cribbage—this was so emotionally painful. The helplessness I felt, not knowing what to say or how to engage with him—it was horrid.

I think about Papa a lot, even all these years later. VTS had me wondering: Could I have used images and VTS to communicate with Papa? With Uncle Tony? One in three seniors dies with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. How are we connecting with them?

Pre-pandemic, I spent time once a week at the Soldier’s Home in Chelsea, Massachusetts. I was invited by their Chaplain, who did a Bible study that was attended by about a dozen service people, most of whom had early to mid-stage Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. The Chaplain wondered if I could do something to help build conversation during the sessions.

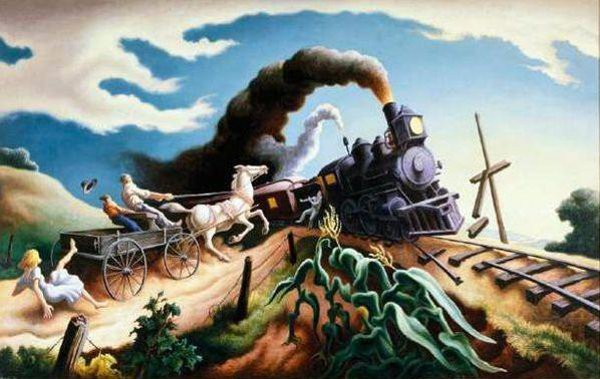

Although we sometimes looked at religious-themed paintings, often I chose secular, narrative works that evoked a feeling similar to whatever passage he was using in that week’s study. One week we looked at Thomas Hart Benton’s The Wreck of the Ole ‘97, a 1943 work currently hanging in the Hunter Museum in Chattanooga, Tennessee. I had the image projected large on a TV screen in front of the group, and they also had laminated copies of the painting on their laps or table for reference.

“What’s going on in this picture?” I asked.

‘Albert,’ a seventy-something year old Navy Vet with dementia was part of the group. “The train is crashing the horse!” Albert cried out. “You’re seeing something about to happen,” I said, “And it may be an accident between a horse and a train. What do you see that makes you say they are crashing or about to crash together?” I paused. It can take a minute or more for someone with dementia to process a question so it’s especially important that we give this time when doing VTS with this demographic.

“The track. It’s broken. The horse is jumping. The man’s hat.” I paraphrased Albert’s comment and asked, “What more can we find?”

Next, Richard piped up, “The girl. That girl is falling and she doesn’t have shoes.”

“You see a figure here behind the wagon and you think she may be falling off of the wagon,” I said. “What do you see that makes you say she might have been on the wagon and now she is falling?”

Although it had started quietly, before long several of the group were animated as they pointed out all the things they were discovering, including:

“The plants! They look like they’re dancing!”

“There’s a ghost on the train!”

“It’s summertime!”

I was beginning to build a strong base of clients. Activity Directors and others could see how the non-judgmental nature of VTS synched seamlessly with what many memory care experts stress are best practices when communicating with adults living with different forms of dementia. Asking one question at a time, repeating what was said (to clarify), and avoiding criticizing or correcting—these are also some of the recommendations for communicating with people with Alzheimer’s listed on the Alzheimer’s Association website. After just a couple of years working with my senior clients, I can see that VTS increases both word usage and retrieval. But it also provides comfort and a respectful enrichment activity that can be used one-on-one or with small groups in a memory care setting.

I am not the first (or only one) to use VTS with seniors who have dementia. There are many museums that, pre-pandemic, scheduled monthly programs, inviting those with dementia to come with a caregiving partner for a VTS experience in a museum space.

But how do we shift the conversation when museums are no longer an option? When they are closed or, even when re-opened, don’t offer their regular programming? How can we continue to provide genuine and respectful art-looking moments for our elderly neighbors, friends, and relatives?

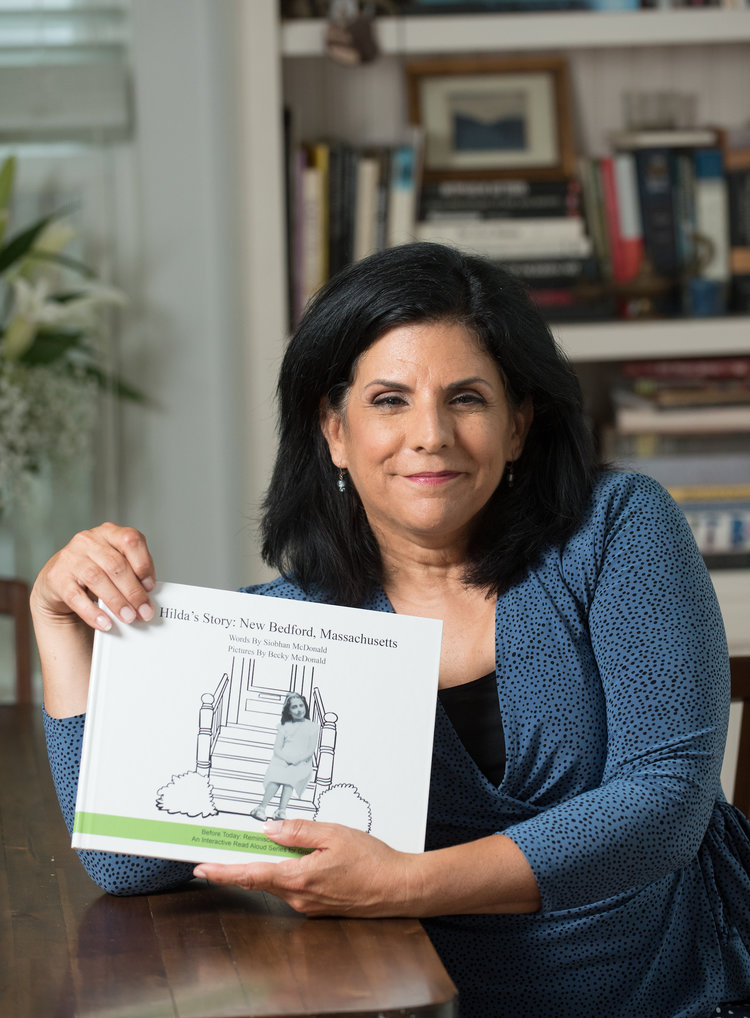

March 2020 was looking to be a most exciting month. My best yet with my new business. I had a dozen workshops scheduled at memory care residences, senior centers, and assisted living facilities. I had also written a picture book the year before, with vintage photos and written prompts, for use by family and staff. I had several book talks scheduled at libraries in Massachusetts and New York. My hope was that the book could be used to help build conversations, when having me come in person may not be possible. And then, it all changed.

What do you do when the world is turned upside down?

Now more than ever, we need VTS. Our elderly people are still experiencing extreme isolation brought on by the pandemic. By the end of the second week of March 2020, facilities were beginning to shut their doors to the outside world. These desperately sad measures were necessary to protect our most vulnerable citizens, but that did not make the heartbreak of trying to imagine how confusing this must be for my clients with dementia any easier.

There were no visitors, no outside vendors coming in to do activities. Many people could not leave their rooms. I received weekly updates from friends who were health care workers, sharing the losses. We mourned via text messages.

So, I started to make short videos that I shared freely on social media. As a child I was glued to the TV every time the show Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood came on. Fred Rogers was a children’s television pioneer in the United States, focused on both the social and emotional well-being of children, as well as their intellect. He is my hero and a role model, continuing to inspire me as an adult. I came up with a theme, being sure to include an art history experience with each video. But this was not the same as VTS. For that, we would need interaction. I missed that interaction with my clients.

Facilitating VTS in new ways

In the middle of 2020, I reached out to every facility (memory care, skilled nursing, assisted living, and council on aging groups that hosted Memory Cafés) I had previously worked with and offered my services via Zoom. I knew there were people in the earlier stages of their dementia who could benefit from a VTS session and, frankly, I was willing to try anything! Thankfully, a few people placed their trust in me and as a result we built some nice little communities of caregivers and their loved ones who look forward to interacting with art and art history through VTS in a Memory Café.

Memory Cafés started over twenty years ago in Europe. Hundreds of Cafés are now held in the United States. They are typically once-a-month, in-person events held in senior centers, places of worship, or other community spaces (some still remain online post-pandemic). The programs are designed to enrich and support both the caregiver and the person living with dementia.

Each Memory Café is unique, but typically includes a social/food component (think cookies and iced tea), a presenter/activity component (a slide show on model trains or perhaps painting a birdhouse), and a chance to check in and get questions answered or be directed to support.

VTS helps us connect with each other.

This brings us to February 2021.

I was presenting a virtual Memory Café program for Elder Services of the Merrimack Valley in Lawrence, Massachusetts. A mix of fifteen people were on my screen, some of them couples (caregivers with the person they are caring for), some individuals. Someone from Right at Home/Boston North (the home health agency who sponsors the program), and a few younger people with various letters after their name (MSW/Masters of Social Work, for example) ‘sitting in’ from connected organizations (other elder service or Assisted Living programs in Massachusetts). There were a few people without video. I wasn’t sure how they were connected to the group.

There are a couple of things I consider when starting a session. First, at the beginning of our virtual sessions, I simply ask if anyone is comfortable with using Zoom (at this point most of my attendees are) and if anyone needs any assistance with sound or video, they can either speak up, wave their arms, or message me in chat. Sometimes people are reluctant to show themselves on video. I do my best to make my sessions a safe, non-judgmental place and do not question their choice about showing themselves on the screen.

It is also important that during this initial welcome I interact with each person, get a sense of who is attending this virtual meeting, and prepare the group for what is to come.

So, before I get into the VTS session, I often begin with a prompt, a question related to the art we will be seeing, that gets people thinking about our theme, makes space for reminiscing, and offers an opportunity for everyone to meaningfully share.

There are a couple of reasons that I purposefully ask a related question before we look at a work of art. I may be seeing this group for one time only. But even if I do get to see them regularly, depending on how much their dementia has progressed, they may not know who I am or recall that we have met before.

Also, because I have other people who are ‘dropping in’ (like social workers or home health aides) I want everyone to participate and not have people feel like they are on the “outside” of the group. I want to combat the social isolation that can happen with dementia. So, before I get into the VTS session, I start with a question that helps us relate to each other. This also helps me to think about how I can potentially guide them to things that may relate in the work they are about to see.

On this day, we were about to look at Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow (1565), and my question was, “What was winter like when you were young?”

One participant’s video was off, so I wasn’t even sure if she was a client, but she did not hesitate when I asked her if she would like to share. “I’m sorry I don’t have my video on…I use oxygen. My hair is a mess. I don’t want you to see me.”

“That’s okay, Dorothy,” I said with an upbeat tone, “We’re just so happy you’re here with us today! Would you like to tell us about what winter was like when you were young?”

“The snow was so high,” she exclaimed. “And we used to go ice skating right down the street.”

“You had a pond or something close to where you lived that used to freeze over and you could skate on it,” I responded, “Did you like to ice skate, Dorothy?”

Dorothy and I chatted for a minute or two and soon others were chiming in. I continued with the program, looking at those snowy hills of Bruegel, buzzing with activity. Several people noticed the skaters on the pond, and we talked about skating and ice games, and we all got wonderfully lost in that shared experience of active looking.

When the program was over, Lyn (from Elder Services) and I stayed on Zoom for a few minutes. She said to me, “Siobhan, I got a text message from Dorothy’s daughter while you were all looking at the painting. She could not believe how much her Mom was talking! She said it was the most she heard her talk in weeks.”

There is so much about VTS that feels like a lifeline right now. Paraphrasing without judgement, the invitation to a shared community conversation, and the feeling that we are all exploring something together, that there is always ‘something more to find,’ this makes me so thankful for the inspiration to find out more about VTS after that long ago day looking at art with those bubbly kids at the museum.

This is why it doesn’t matter how many times I’ve looked at a certain work of art: the magic of witnessing the moment someone gets excited about something they see—that moment is unique to each group. No matter what challenges they are facing in the present, these shared experiences are enriching, comforting, and life affirming. This is VTS.

Questions or comments? Contact us.