In my experience as a classroom teacher, I found that VTS was a great place to let students engage in productive discussion, teach them about forming an argument, and then transfer those skills to other content areas. The openness of the VTS format—where the image can be accurately interpreted in multiple ways and people can explore different perspectives—is different from some of the other academic content areas in elementary school, where there can really be only one logical argument. VTS was the first place that I could actually show students that, when you are making an argument, what makes it powerful is the background knowledge that you bring to the table to explain your interpretation. The reasoning element of the curriculum is very strong.

From 2006–2015, I taught in Oakland, California, at New Highland Academy, a Title I school with predominantly African American and Latinx students. 1 Between 2010 and 2015, I looped with my class, meaning that I taught both 4th and 5th grade with the same group of students. At that time, as a faculty, we were working to support our students to develop academic discussion skills and adopted VTS to help support that practice.

One day—after we had been using VTS at our school for two or three years already—we were discussing a painting by Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (1939). Students were debating back and forth about what Frida was going through in that moment and different students were interpreting the picture in different ways. One student had done some reading about Frida Kahlo and added their background knowledge to the conversation. They named a book that they had read and made connections to that text. Another student, who was seeing the school counselor at the time, was able to build on their own personal experience and refer to their conversations with our school counselor in their interpretation of the image.

That conversation was so rich and powerful that it really stood out to me, especially the way students could argue for a particular claim in the image. After hearing this, I had an epiphany: I realized I could teach argument writing using VTS as a vehicle.

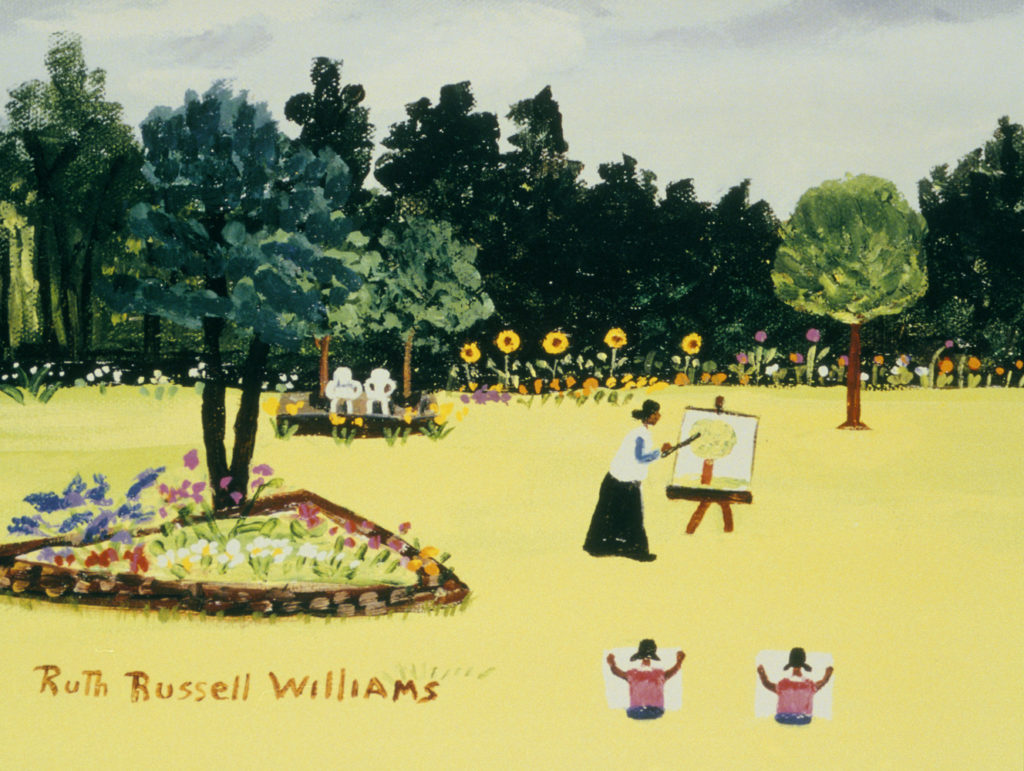

I spent the summer working on this idea, thinking about how to stretch my VTS time into a two-day writing process where students would use the VTS discussion to learn argument writing, specifically how to support their claims with evidence. I decided we would use one VTS image per a week, spending two days on each image.

On the first day, we did regular VTS and then after the discussion I took notes on what claims came up during the conversation and organized these into different categories of claims and evidence. On the second day, students would write a paragraph based on their claim.

To begin this process, I asked them to be very clear in what they thought was going on in the picture. We started talking about how, once you identify what’s going on in the picture, you are making a claim for your argument.

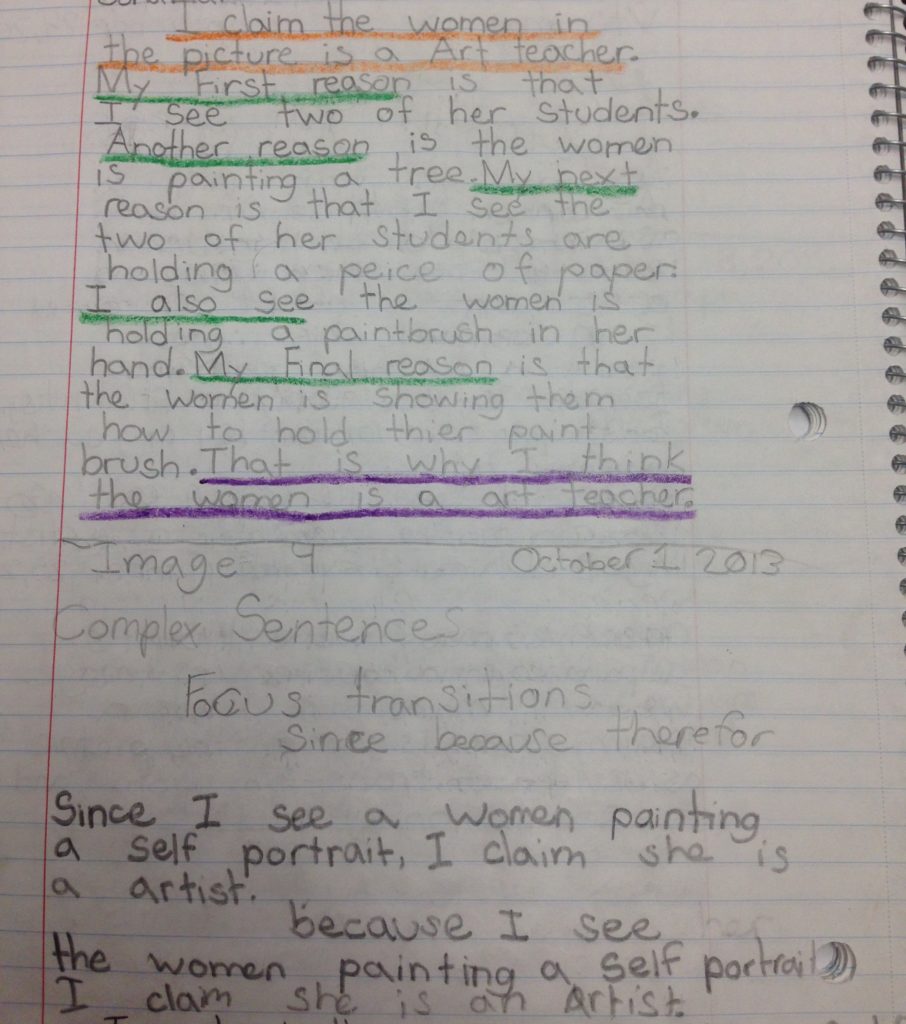

From then on, after the VTS discussion, before they could get up from the carpet and go to their seats, they had to name precisely what was going on in the picture to let me know that they were clear on what their argument was. After they took their seats, I would leave the projected image up, and they would write. At first, this was just a paragraph: I asked them to find three to four pieces of exact evidence—things they saw that made them make that claim—and then write a conclusion statement.

We practiced just doing that for a good month, going from the image discussion to the paragraph and pointing to exact evidence in the picture. Once I knew students could do a solid introductory paragraph with a claim, then we started to stretch our essays.

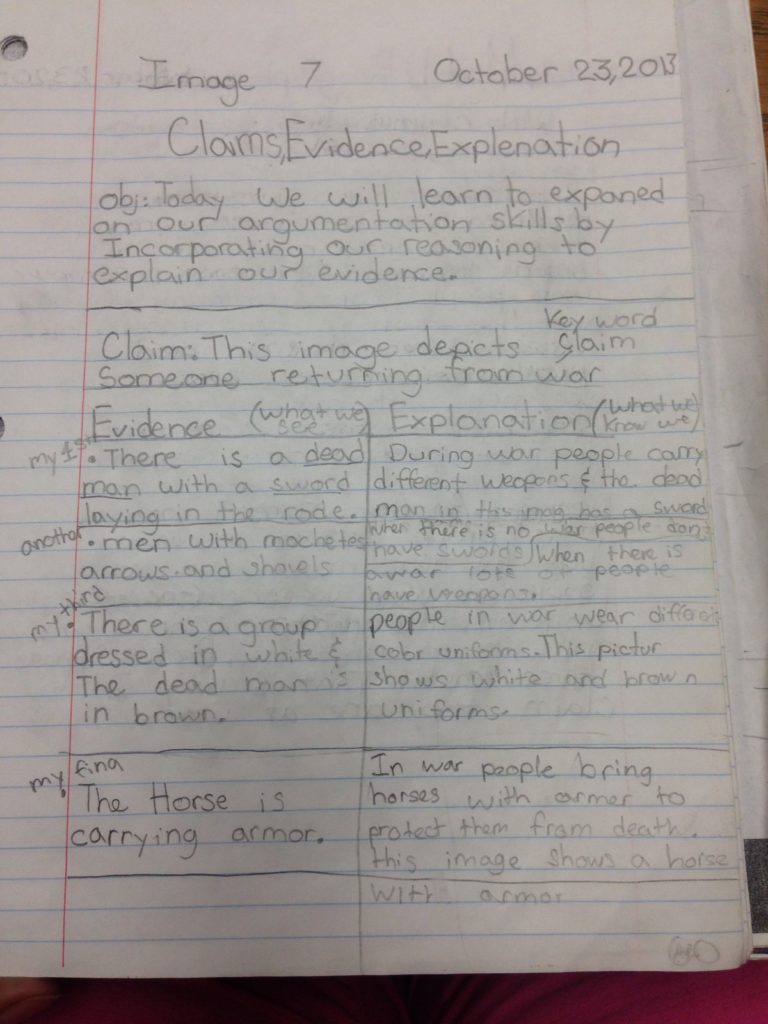

For this next step, I modeled argument writing for the class: we had a VTS discussion and then, just for the purposes of writing the model, we came to a class consensus about what students thought was happening in the picture. To do this, we went back and forth between perspectives until everyone agreed we could write from a particular point of view. Next, we wrote our claim statements together, chose our evidence, added to that evidence, and then wrote the conclusion.

Next, I talked to them about reasoning, as in: when making your argument, you may see things differently, but you have to be able to explain your reasoning. We would pick something particular in the image and name it however we saw it, such as “I see a man in the image carrying a weapon, a sword or a knife. Based on what I know about war, from reading my history books and seeing other images, I believe this man carrying this weapon is on his way to or from a battle.” Then, we would say, “Another reason I think this is something that has to do with a battle is… .” This way, we would expand our pieces of evidence.

Then we would go to another part of the image, for instance, “Also, in this image there are horses.” We built our argument by unpacking different parts of the image. To explain our reasoning, we would bring in our background knowledge, such as things that we had read or seen or anything that was present in the students’ body of knowledge that could help explain our interpretation of that piece of the image. To conclude the essay, we came up with a sentence to really drive home the idea that the combination of all these pieces makes us think that this images depicts whatever the claim was.

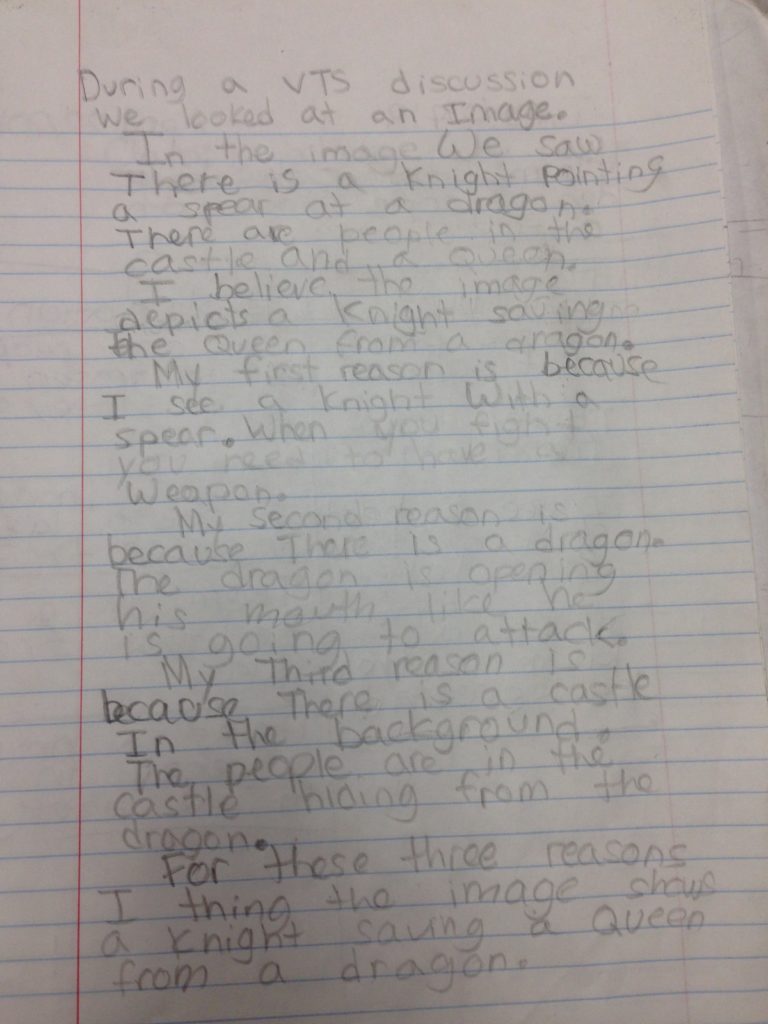

In this way, we modeled this process, unpacked the model, and put the model up for all to see and refer to. Then with the next image, it was the students’ job to try it out. Once they tried it out on their own, I read all of their arguments and noticed that their essays jumped right into their claims, but did not offer a description of the image itself. I realized we needed to start with an introductory paragraph. This led me to help them develop an opening where they would provide a brief description of the image before diving into their claims and evidence.

This was a great teaching tool: later, when we began to write arguments about stories we had read, students’ knew to start with a brief summary before going into their argument. They knew to think to themselves, “What are the main points we want to let the reader know before we make our claims and explain how we are interpreting the sentences we are using for evidence?”

One of the benefits of teaching argument writing using VTS was that I could focus on teaching the mechanics of writing itself, because it did not matter so much to me what they said about the image. After all, at the end of the day, we all see these images in different ways. As long as they could explain their point of view and connect their personal experiences to it, I did not have to correct for content; I could just focus on their tools for putting arguments together.

My thinking on the subject was like this: the skill of writing out and building an argument needs to be taught in and of itself—that was the real objective of my lesson. Previously, if I were trying to teach argument alongside how to comprehend a book or a science experiment, their argument writing would usually get short-changed. With VTS, however, I could teach argument in a place where they naturally had opinions and wanted to express their points of view.

I also found that the images in the VTS curriculum were supportive and that there were enough of them to take us through the whole year. The variety of images supported different students at different times, so that if a student wasn’t jazzed about one image, later on they would connect with another one.

To help improve our writing, I would use certain students’ writing as models, asking everyone to read and reflect on it before working on the next one. I need to note that at the time, our school had a teacher inquiry group and I was looking at this practice during my teacher research time. That is, in addition to the VTS training we were receiving, once a month we also had a facilitator from Mills Teacher Scholars of Mills College in Oakland that would guide us through about two hours of teacher research. As part of this process, we would have work time: 30–45 minutes when we could look at student work, talk about it, think about where we were in our practice, and think about what we needed to do next. So I had time set aside to focus on improving this practice. This was a wonderful program: if I had an idea that I thought could have a strong impact on my practice, I would think about it, try it out, and then bring what I had to that space to explore making it better. The first time you try something out, it never works perfectly, but I would keep bringing it back and tweaking it.

Once a month, I could lead a VTS discussion, bring the students’ writing to the inquiry group, read the whole class set, and be able to find someone who had really done some interesting things with their writing. Then I would take that back to the class and say, “Let’s read this person’s essay and try to find some of the cool things that they did with reasoning or with organizing their paragraphs.” We would read those examples and use them as inspiration for things to try when we looked at the next image.

As a result of this process, I saw students’ writing improve by leaps and bounds.

I noticed a couple of important things about VTS that made all this possible:

1. We could have productive discussions that went back and forth without any student feeling shut down by a need to come to that logical, “right” answer. If we had been arguing about history or a science experiment, eventually, there would have to be a perspective that would emerge as the most logical one. The way VTS is set up, however, there are multiple valid arguments, so students can write from different perspectives using the same set of evidence. The openness of the VTS format was really a gift.

2. During VTS discussions, because they were utilizing their visual ability as a foundational skill, students were engaged in a complex text. Later, they could transfer those skills to reading and other subjects. This was part of the reason I ended up putting argument writing into the VTS lessons.

From there, we moved on to other content areas, such as poetry, history, and social studies. For social studies, at the beginning of each unit we would look at images in the curriculum through what we called a “VTS lens” to help us build our arguments.

We would pick a pivotal image—either from the book or connected to the book—that we would use to open the conversation as a discussion starter. This gave us a space where students could pull from their background knowledge in order to explain how they were interpreting the image. It provided a great opening conversation where they could start to develop their arguments and I could assess what their background knowledge about the subject was and then we could move forward into our unit and the main question that would guide our unit investigation.

For history and social studies discussions, I also added one, more specific question. I would let the students know that for these images, we have to think about more than just the perspective of the artist, we have to think like a historian. Based on work I had done with Mills Teacher College Inquiry Project, I added a fourth question: “What might a historian ask about this image?” or else I would say, “If we put on our history hats, what questions might we have?

Over time, their critical thinking skills deepened and their writing fluency increased dramatically; they were able to get much more down on the paper. One of the aspects of VTS that was critical to my discovery of how to use it to teach argument writing is the second question. When you ask a student, What do you see that makes you say that? it brings the criteria for their reasoning to the forefront. If you look at the image and you see a bird sanctuary, but I see a zoo, when I ask What do you see that makes you say that? you have to bring up your personal experiences, the things that you’ve done that make you interpret the image in that way. If I say the image is something else, then I have bring my personal experiences that are making me interpret it in a different way.

One of the hardest things to do as a teacher is to help students present their reasoning. All too often, if you ask a student “Why do you think that?” they will say, “Because it is!” Part of the importance of VTS is what I call “moving beyond because”—to get students to supply something logical on the other side of that “because.” If you look at a picture and see a bird, but I see an airplane, then I need to explain, “I think it is an airplane, because of this reason.” The second question, What do you see that makes you say that? trains them to provide that evidence. It also provided us with a smooth transition into thinking about counter-claims, i.e. “It’s not a bird because of this reason.”

Over time, I saw significant gains in students’ literacy scores, but more importantly in their confidence as critical readers and capable writers. Of course, I cannot point to one specific factor, because there are many different things that have an influence on a school, but the long-term effects of students’ ability to engage in academic discussion, their understanding that people have a perspective, and that there is more than one valid perspective on any given subject greatly contributed to their academic achievement. Using VTS as a school community was one of the contributors to getting New Highland Academy out of “program improvement” as defined under No Child Left Behind. We were one of the few schools in Alameda County to achieve that; they even wrote about it in the newspaper.

The way VTS facilitates social emotional awareness, self-awareness, and argument is also very powerful. VTS trains the teacher to paraphrase, to remain open and accepting, and not to make any argument seem more valid than another. Students learn to have academic conversation, to be aware and self-aware, to argue without hurting anyone’s feelings, and keep it in an intellectual space, even when it’s a heated debate. Even when students felt strongly about something, they held themselves to the structure of the conversation and could use that structure to build, to agree or disagree. They learned to have strong engagement with each other.

Having someone teach you these facilitation moves and have you practice them is a really strong part of the VTS program. There are certain things I learned directly from the VTS Trainer working with our school, Liz Harvey. I knew I wanted to create an environment or hold a space for students to be able to have different perspectives, but I hadn’t been taught the facilitation moves to make that happen. Then along came VTS and it taught me the facilitation moves that I needed to make this space happen. I could then teach my students the argument building that they needed to do so that they could engage in the space successfully. Learning how to paraphrase in different ways, call out particular vocabulary, or give a word or way of thinking back to students—all of those VTS facilitation moves helped me keep the space civil, keep an intellectual dialogue happening, and keep students engaged.

In closing, I want teachers reading this to know that in creating this, I had fun; it didn’t feel like work. But an important thing to understand is that I developed this practice over the course of a year. I did not go in on the first day, say, “Let’s do VTS and write an essay,” and then get a perfect essay back from my students; it took time. It took a lot of listening, looking at student writing, and then connecting that to the building blocks of argument and reasoning. I had to figure out how to tease those things out and connect them to what was happening in the classroom, to learn to take what students were organically saying and writing and clearly connect that to the building blocks of argument. For instance, during my paraphrase, I might say, “What you just did was, you explained your reasoning.” Or, “You just presented us with your evidence.” Before the VTS discussion, I would think, “What is the next piece of argument I need to be listening for?” so that I could highlight it.

As told to Madison Brookshire

Questions or comments? Contact us.

Footnotes

- 1 - New Highland Academy also has a bilingual strand from K–3 that then moves into “sheltered English” classrooms in 4th and 5th grade, or English immersed in English Language Development. We also used VTS to support English Language Development.