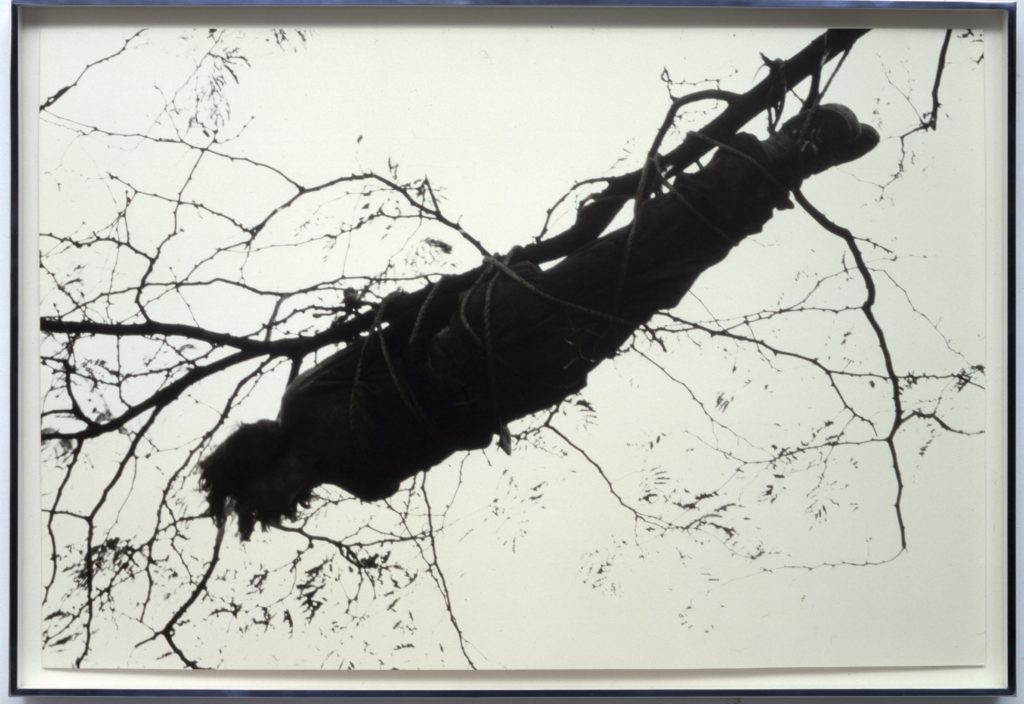

On a recent gallery tour at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), I led a discussion with fourth graders at an untitled photograph by Charles Ray from 1973, in which the artist is suspended in a tree with rope. One student shared that the person tied up in the tree reminded them of hanging by suicide and lynching, recalling how “in the old days people were hung when they did something very bad.” Several thoughts raced through my mind as I grappled with how to proceed.

Charles Ray, Untitled, 1973, black and white photograph, mounted on rag board; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Gift of Lannan Foundation; ©Charles Ray, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

I thought about how lynching is a racist and horrendous act of violence that still occurs in America today, such as the murders of Lennon Lacy in 2014, Dayne Jones in 2018, and Taemon Blair earlier this year. 1 I was pained by the discrepancy between the realities of lynching and the uninformed conventional wisdom, or widespread beliefs, reflected in the student’s knowledge. But I also asked myself: could further discussion about death and hanging be harmful to these students I had only known for 20 minutes? And/or open a wound that I am incapable of acknowledging or soothing in an hour-long tour? My paraphrase was concise and did not include the second VTS question, What did you see that made you say that? I simply said, “This artwork is reminding of you of violent ways people may be hung in trees such as lynching and suicide. What more can we find?”

Looking back, I could have inserted an “FYI (For Your Information)” into my paraphrase, a strategy we developed at MOCA that Jeanne Hoel describes in this essay, that offers a gentle re-contextualization of harmful comments. 2 However, in those few seconds, I had weighed my perception of the group’s level of racial awareness, my capacity to provide accessible and non-violent language about lynching on the spot, and the purpose of my role: to facilitate a discussion about artwork that centers students’ thinking.

My choice in that moment was that of a trained VTS facilitator who carefully moves on to avoid furthering the potential harm of a tricky comment and keeps the dialogue centered on the artwork and the group dynamic. It was a choice of an experienced constructivist who recognizes that unpacking the racist history of lynching would prioritize my own teaching agenda and was likely developmentally inappropriate. It was not a choice, however, of an educator who works against oppression because my choice kept the violent realities of lynching silent and the racism perpetuated in the student’s understanding invisible. The student’s description of lynching, which was presumably unknown to the student, was a narrative that upholds white privilege and erases the death and suffering of countless black people who have been killed. How often do my choices as a “neutral” and student-centered facilitator uphold dominant narratives, silence marginalized histories, and perpetuate oppression?

As Kabir Singh calls out in his essay, while VTS strives to create equitable learning spaces it is not explicitly anti-racist. VTS asks facilitators to be open and accepting to the comments made by participants and to paraphrase without expressing judgement. Potentially, this leaves room for violent comments to be said and heard without intervention by the facilitator. Violence that appears in discussions includes ideas and language that inflict mental and emotional harm and/or perpetuate forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, and classism. As a result, VTS does not always align with my intentions to dismantle oppressive structures of power. At times, the VTS method, as it has been taught in the past, asks me to uphold the very forms of oppression I am fighting against. At MOCA we have developed a few strategies to combat the potential of VTS to be passive; however, these strategies must be paired with a disciplined and ongoing commitment of the facilitator to become conscious of how all forms of oppression exist in society and within oneself. As VTS facilitators, it is our responsibility to engage in ongoing research and self-reflection so we do not perpetuate harm.

VTS recently moved away from using the word “neutrality” to describe facilitation because being neutral, at times, can be irresponsible. VTS now describes neutrality as “non-judgemental” or “open and accepting.” The term refers to the facilitator treating all comments equally, but also points to the accuracy of a paraphrase and means not adding to or changing a comment. In both facets of paraphrasing, being neutral leaves space for the perpetuation of oppressive language and ideas because a facilitator’s neutral paraphrase may validate and reinstate violence within a comment.

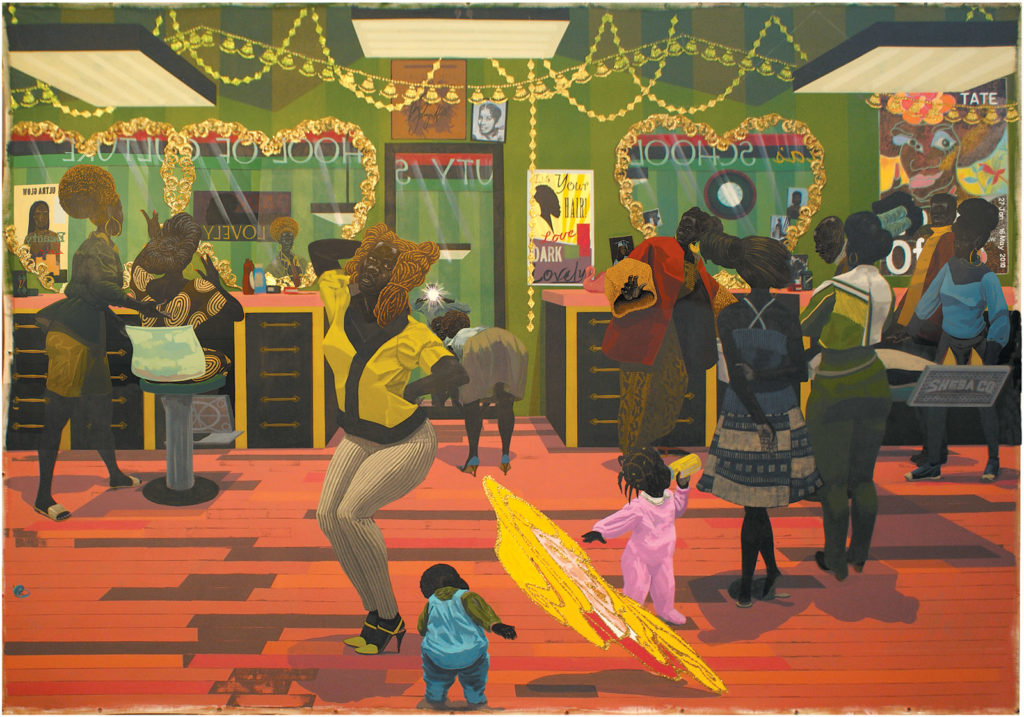

The idea of neutrality in VTS as problematic became apparent when the Kerry James Marshall: Mastry exhibition was on view at MOCA in 2017. Jeanne Hoel and Michelle Antonisse write in depth about the preparation and techniques we developed to facilitate VTS discussions in the racially charged exhibition. Marshall’s work challenges perceptions of black identity through life-size paintings of black figures engaging in daily activities. His work confronts racial stereotypes and elicited countless comments tinged with racism. We quickly learned that paraphrasing neutrally upheld and reinforced the white supremacist ideology concealed within comments. As Hoel and Antonisse share, the work we did to address the racism that surfaced on tours included months of reading critical race theory, vulnerable group reflections, and the painful inner work of unlearning racism within ourselves.

Kerry James Marshall, School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012. Acrylic and glitter on unstretched canvas. Museum purchase with funds provided by Elizabeth (Bibby) Smith, the Collectors Circle for Contemporary Art, Jane Comer, the Sankofa Society, and general acquisition funds, 2012.57. © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of Kerry James Marshall and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY.

Marshall’s exhibition was a pivotal point in my teaching practice. Ruth King, an author and meditation teacher who sees racism as a disease of the heart, describes white supremacy as “an intravenous drip into our consciousness for generations; a part so integral to US history and culture that it is not in our consciousness to notice it.” Ruth calls for us to “wake up to how it is expressed and to discern its impact.” 3 What does it mean to be neutral in a non-neutral, hetero-patriarchal white supremacist society? Neutrality can be harmful because we may be unaware of how a comment or a paraphrase can reproduce violence, especially if we are unaware of how our thoughts and behaviors have been conditioned by white supremacy. Facilitating VTS in Marshall’s exhibition illuminated my own conditioning and woke me up to my responsibility as an educator to equip myself with tools and knowledge to battle the insidious racism programmed in my mind and in the minds of others. Marshall Rosenberg, the American psychologist who developed non-violent communication declares that, “We are dangerous when we are not conscious of our responsibility for how we behave, think, and feel.” 4 When we are unconscious of our own biases and internalized racism, ageism, xenophobia, misogyny, etc., we are unconscious to how our facilitation choices may uphold and perpetuate oppressive structures of power.

Violence that emerges from unconscious conditioning has become further apparent to me through the work we are doing at MOCA to be gender inclusive. We are studying queer theory and critical trans politics and placing attention on how gender is coming up in our gallery tours so that we can workshop ways to be more inclusive. We are in the process of this investigation and have implemented some steps to be gender inclusive, such as including our pronouns on our nametags and refraining from using she/he pronouns when addressing or refering to students or artists. 5 I am astounded by how often I verbally assume the gender of students and how often students verbally assume the gender of artists. The volume of these occurrences is especially startling because they have always been occuring, only I was not yet conscious of my conditioning to assume gender and unaware of the great harm misgendering a person can cause. 6

Learning about gender has equipped me to insert more societal frames in my paraphrasing. Societal framing, as described by Michelle Antonisse in this article, is another strategy we developed at MOCA to address harmful comments by “paraphrasing the underlying assumptions of the comment.” 7 For example, I recently paraphrased a comment by saying, “You see this as a drawing of a woman because they are possibly wearing makeup and in our society we are conditioned to associate wearing makeup with being a woman.” If I had paraphrased, “You see this as a drawing of a woman because they are possibly wearing makeup,” I would have allowed the binary notion of “only women wear makeup” to remain an unchallenged truth.

Because there are no wrong answers when making meaning about art, VTS supports giving voice to multiple perspectives. But what about perspectives that are charged with oppressive violence? bell hooks states that “no education is politically neutral.” 8 When we neutrally paraphrase and do not re-contextualize harmful comments in a discussion, we are complicit in the violence of those comments. Further, as a woman of color, when I am neutral and remain silent as a facilitator when racism or sexism or any “ism” that marginalizes my identities emerge in a discussion, I am colluding in my own oppression.

So then, beyond the mechanics of VTS, what are our responsibilities as facilitators? Paulo Freire asserts that, “Those who authentically commit themselves to people must re-examine themselves constantly.” 9 To be an anti-oppressive educator, student-centered teaching not only centers students’ thinking, but also students’ consciousness. We must constantly scrutinize our own conditioning so we can be an intervention to, and not a tool of, societal conditioning that maintains oppressive thinking in the minds of our students. As VTS facilitators, we have a responsibility to do ongoing research and inner work to unlearn oppression so that we can oppose violence and not perpetuate harm.