In 2018, I led a VTS training for dual language elementary school teachers in Cudahy, California. As I started to work on how I would translate VTS into Spanish, I remembered my own experiences as a child learning two languages at once. I reflected on how much richer and more empowering it would have been to have had someone validate my “native tongue” in school. I then thought about how the history of my “native” language affected the way I even perceived language. The Spanish language is used by almost half of the world and in almost every country south of the United States. By 2050 the United States will have an estimated 138 million Spanish speakers and will be the largest Spanish-speaking nation in the world.1 However, this generalization does not account for the diverse dialects and other languages that Spanish-speaking migratory people will be bringing with them as well.

As I continued to reflect, I also thought about the history of conquest in the Americas; after all, my “native tongue” was never really my native language. Post-conquest, the Spanish language was forcibly imposed upon the indigenous peoples of the Americas as a colonization and conversion method. My parents and grandparents on both sides are from a pueblo, or town, called Panindícuaro in Michoacán, Mexico. My real “native tongue” was Purépecha, a language of the Purépecha people, who continue to practice and speak their native language today. Although I had no words in my vocabulary that originated from the Purépecha language, I had some words that were remnants of another dominant group in Mexico: the Aztecs. Nahuatl is the language that was used by the Aztec people of Mexico and still survives today, 500 years after the conquest. I realized that my Spanish was a language that I acquired because of colonization and that if I had native words in my vocabulary, there was a high probability that there would be students like me, who had a different way of speaking Spanish or, possibly, an indigenous language.

At this point in my process I realized that conducting VTS in Spanish would not be as simple as a quick translation. So my questions in this training became, How do I best support students who are learning Spanish and/or possibly speaking in their native tongue? and, How do we as teachers both support language development and deconstruct the structures of language that erase histories? For me, my would-be native language was completely eradicated by colonization in Mexico and my Spanish was diminished by assimilation in the United States. bell hooks touches on the topic of language as a tool of resistance, but also of trauma, in her essay “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness” when she repeats, “Language is also a place of struggle.”2 However, within this struggle of language there is an opportunity for us to connect and learn from our students.

Coming into the training, I decided to start the conversation with teachers by discussing how Spanish is rich in meaning and is completely different based on where you live around the world, or even within Los Angeles. We went over how VTS is a tool to have students expand their minds and become better critical thinkers: it was essential to let teachers know that VTS was not designed to teach students Spanish, but to help them build critical thinking, communication, and collaboration skills. Although I knew there would be a long road ahead of us, our first step was to translate the VTS questions themselves.

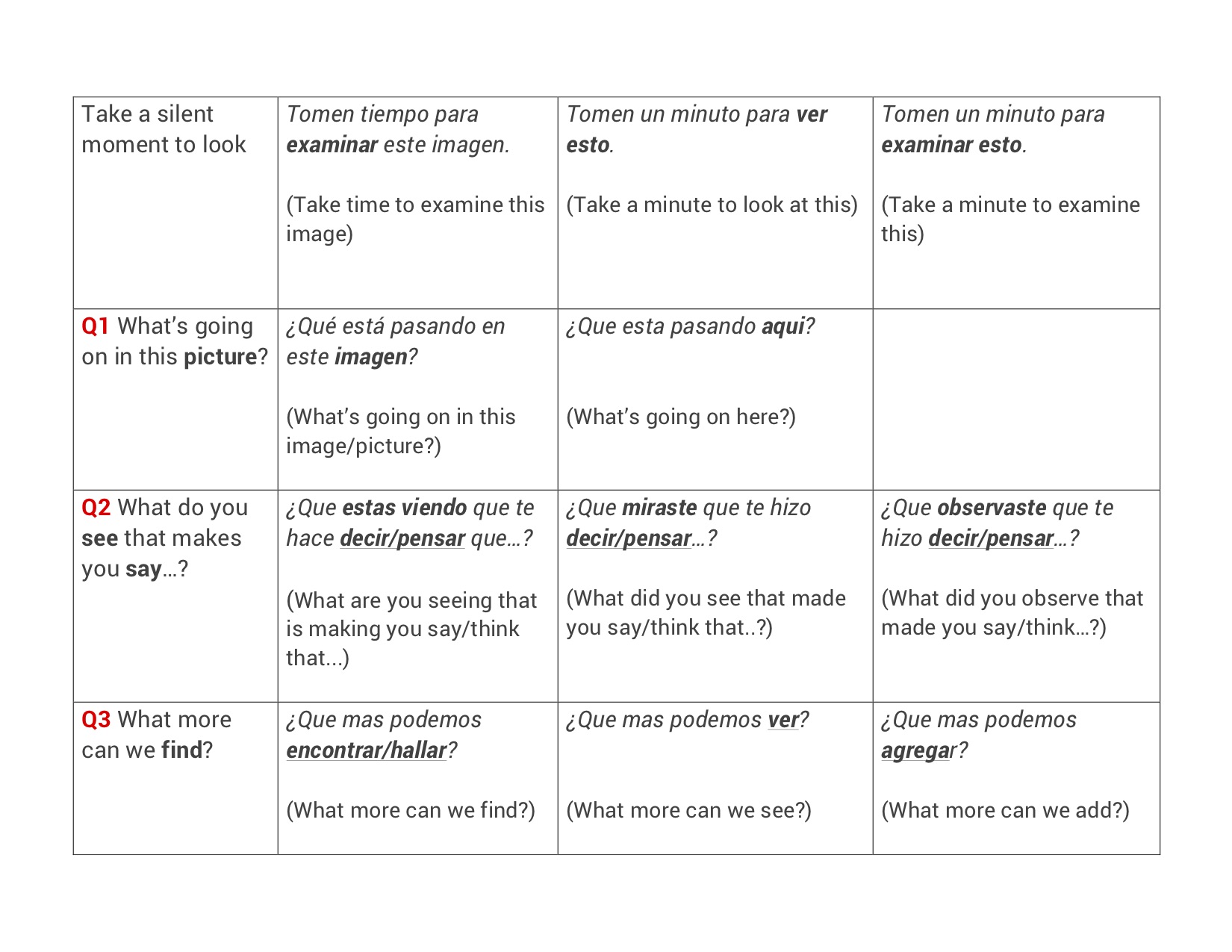

The figure above illustrates how difficult it was to simply translate the actual phrasing of the VTS questions. It quickly became apparent that there were many ways in which to say one word, but, of course, we had to start somewhere. An important discovery that we made was that it was imperative to first set guidelines and expectations to illustrate that VTS is not about right or wrong. When conducting VTS discussions in English, when we say, “There is no right or wrong,” we are perhaps thinking of the content of students’ comments. In Spanish, my concern was a sense of right or wrong within the language itself and the words chosen to describe objects. Teachers would need to listen attentively to comments with an open mind, but also be sensitive to nuances of language. As an example of some of the nuances we had to consider in our translation process, I’ve outlined some of the choices we made in translating the questions below.

Silent Moment: I made a conscious decision to say examinar (examine), as opposed to saying mirar (look) in order to ask students to thoroughly look at the imagen (image).

Q1: The phrasing in this question is a little bit different than what we see in English (What’s going on in this picture?). Our concern with this question was using aquí versus en este imagen. We decided if we were observing a sculpture or three-dimensional object, we would use “aquí.” However, if we were looking at a two-dimensional object, we would use “en este imagen.”

Q2 and Q3: The variations of translations of “see” and “find” provided me with too many different iterations of possible questions to try. Encontrar is the literal translation for “find,” but at times it can seem like the facilitator is asking you to find something else, as if there must be something more. A teacher at Ellen Ochoa Learning Center, began using the phrase, “¿Qué observaste que te hizo decir…?” and it worked well in her classroom. She also presented the idea to use agregar (add) and observar (observe). The students were not seeking to please the teacher by simply adding to one observation, but expressed individual observations.

When it came to paraphrasing, there were many more aspects to consider. As I stated earlier, the goal of VTS is not to teach the “correct” Spanish, often associated with Spanish from Spain. Interestingly enough, “correct” or “academic” vocabulary always seems to be at the center of discussions on how to conduct VTS in Spanish; sometimes people will use the term “proper” versus “improper,” which connotes superiority and inferiority. As I thought about how to address these ideas of “right” or “wrong” Spanish, I thought about my own relationship with the language.I am a first generation Mexican American and an English language learner. My parents had an elementary school education, but they knew the value of learning two languages. At a very early age they had us read the only book in the house that was in Spanish, The Bible. If you have ever read or tried to read The Bible, you will understand how its language was vastly different from the one my parents were speaking at home. I knew the difference between the words that were written in books and the words I used in my life. I felt the weight of my Spanish, when teachers, parents, family, or friends would say that our Spanish was mocho, slang for a “broken tongue.” What they never considered was that I lived in two worlds: one at school, where I was afraid to speak English because I was still learning, and the other at home, where I was afraid to speak Spanish because it wasn’t good enough. This relationship with Spanish would continue as I entered into higher education.

While in college, my “correct” use of Spanish was put to the test. When I asked my friend for a fork, the word I used was trinche, a word that I had used my entire life. My friend looked at me strangely, started laughing, and called me an India. Indio/a is a divisive term that intersects race and class and is used throughout Mexico. It directly translates to “Indian” and is a term historically used to insult someone who is brown, implying the person is uneducated and from a lower economic class. You see, my friend knew the “correct” term for fork and that word was tenedor. Tenedor means “holder” and translates directly to English as fork. Trinche is a Spanish/Portuguese word that was used in Latin America; its root means to shred or tear. In my case, the Spanish from Spain was the dominant language that became the “criterion against which the level of civilization of the colonized [myself] would be measured.”3

This interaction made me consider what other words I had in my language that were not common among the general Spanish-speaking community. For example, my parents taught me the words guajolote for “turkey” and tecolote for “owl.” Both words originate from Nahuatl: Guajolote is the Spanish adaptation of a Nahuatl word huehxōlōtl and tecolote is the Spanish adaptation of the Nahuatl word tecolōtl. In Spanish, the “proper” words are pavo and lechuza or búho, respectively. I did not know this growing up. To me guajolote and tecolote were just the words for “turkey” and “owl.” Other people’s prejudices had confused me and made me believe that my Spanish was a product of two uneducated parents. I didn’t realize these adaptations of the Nahuatl language were not deformations of the Spanish language, but were forms of resistance. Nahuatl is a language that survived years of repression and erasure. It wasn’t until ten years later that I would discover these words of mine had actually survived hundreds of years of colonization and found their way from Mesoamerica to my hometown in Terra Bella, California. However, after being told my Spanish wasn’t academic, I would only use it when it was necessary. To illustrate how incredibly complex and diverse the Spanish language is throughout Spanish-speaking countries, I am providing a very small list of just some examples of differences in language for two simple words: “Grass” (Figure 2) and “Corn” (Figure 3).4

As I reflect on what it means to VTS in Spanish and the heavy history that comes with it, I remember my first time conducting a VTS discussion in Spanish. I was extremely nervous because of my own history with the Spanish language, but I entered the space with vulnerability and began my group session with:

“Yo aprendí español cuando estaba chiquita, pero con el tiempo se me ha olvidado algunas palabras. Pero para eso están ustedes para ayudarme y yo a ustedes.”

“I learned Spanish when I was little, but with time I have forgotten some words. But that is why you are here, to help me and I you.”

VTS in Spanish is not as easy as translating a few questions. What I’ve learned is that there is not one way to conduct a VTS discussion in Spanish. The many nuances in the language that are the result of geography, colonization, local dialects, and indigenous influences result in potential misunderstanding, but also potential for new understandings. VTS in Spanish presents a unique challenge to teachers: to learn more about the demographics of our students so that we may begin to understand them better.

Questions or comments? Contact us.

Footnotes

- 1 - Chris Perez, “US Has More Spanish Speakers Than Spain,” New York Post, June 30, 2015, https://nypost.com/2015/06/29/us-has-more-spanish-speakers-than-spain/.

- 2 - bell hooks, Yearning: race, gender, and cultural politics (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1990), 146.

- 3 - David Gonzalez Nieto, "The Emperor's New Words: Language and Colonization" Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 5, no. 3 (2007): 232, https://scholarworks.umb.edu/humanarchitecture/vol5/iss3/21.

- 4 - Translations: Wordsense https://www.wordsense.eu