For those of us working in health settings and health education, we have seen firsthand the need to find ways to not just survive, but to thrive within personal and professional spaces that are steeped in ambiguity and complexity, and this has been heightened by the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Visual Thinking Strategies offers us, our university students, and our health colleagues an enriching space where we can experience firsthand how to navigate individually, and collectively, through explorations of uncertainty, all within a social emotional learning framework that feels safe, fair, and open to all. As the past few years of adapting to the global pandemic continues to teach us, now more than ever we need educators and health professionals who embody the capabilities and the flexible mindsets to work collaboratively, critically, and creatively within teams and communities to positively support individual and population-level health initiatives.

For example, in New Zealand pharmacists are increasingly working with other health professions such as community nurses and family medicine doctors, combining their individual expertise and ways of thinking together, to provide holistic and tailored care and services to people, families, and communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic pharmacists in New Zealand pivoted rapidly to provide extensive vaccination services which required service reconfiguration, collaborative working with other parts of the health service and the development of new skills. Our pharmacy undergraduate students describe varied “holistic” benefits to their personal and professional development, through participation in Visual Thinking Strategies sessions.

I think my ability to link different reasons as to why an individual’s health may be compromised developed my “big picture” thinking skills. There was a photo about alcoholism and gambling that struck a lot of thought in me about how so many different things in life can contribute to one outcome.

Who We Are and Our VTS Participants from Health Roles and Pharmacy Education

We—Kim Brackley, Trudi Aspden, and Lynne Petersen—have been on our own personal and joint professional VTS journeys together since 2016. All three of us have evolved our individual practices and collaborative explorations in leading Visual Thinking Strategies discussions where we live in Auckland, New Zealand, within health and pharmacy education settings since our initial shared two-day VTS Beginner Practicum training led by Heidi Arbogast in February 2016. For that reason, we have chosen to write our reflections together on our experiences as facilitators of learning through VTS in our hospital pharmacy and university health education settings.

Kim works as a pharmacist and manager of pharmacy education in Auckland City Hospital and Trudi and Lynne are university educators working within the University of Auckland’s undergraduate pharmacy program. Trudi is also a pharmacist with diverse community pharmacy experience. We have come to see VTS as a core foundation in our clinical spaces and in our undergraduate teaching. It offers potentials for us, our colleagues, and our students to respectfully communicate with and understand patients as individuals with their own personal health perspectives, beliefs, and behavior drivers.

Trudi Aspden, Kim Brackley, Lynne Petersen

Auckland, New Zealand

Lynne and Trudi have annually facilitated VTS sessions for pharmacy students who are just entering the pharmacy undergraduate program. Each student is scheduled to attend ten 30-minute VTS sessions (two written and eight oral) over two semesters as part of their compulsory courses in the program. Group size is generally between 8 and 15. After the first two years of implementing VTS, the inclusion of VTS in the BPharm program was evaluated via an anonymous e-questionnaire available to all participants.1 The findings confirmed the benefits of VTS for our students’ personal and professional development through collaborative learning discussions they indicated were different to all other parts of our curriculum. One pharmacy student observed about their learning through Visual Thinking Strategies sessions:

It was interesting and refreshing and was like a breath of fresh air compare[d] to other courses.

Kim facilitates VTS with a range of healthcare professionals including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, nurses, doctors, and other healthcare workers such as human resources or quality improvement staff. Groups sizes have varied considerably to reflect the situation and needs of the staff involved in the VTS discussion.

Auckland City Hospital

University of Auckland

Since 2016, we have worked in our areas of hospital healthcare and pharmacy education to explore potentials of VTS to enable growth of a “multi-dimensional mindset.” A “multi-dimensional mindset” involves an open disposition combined with the capacity to link different concepts while incorporating varied perspectives. We see this as being essential for development of health professionals who can deliver equitable, safe, effective, and compassionate healthcare. In our eyes, the global pandemic has only reinforced how vital Visual Thinking Strategies is within our teaching and clinical spaces. We also believe that it supports the development of skills and dispositions enabling positive contributions to the lives of our VTS participants, and through them, to the health of individuals and communities seeking healthcare. In addition, it supports our own development with respect to our open-minded attitudes, and our ability to be flexible in our thinking in the moment. It has also strengthened our non-judgmental listening skills and our facilitation of many situations. As one of our pharmacy students expressed about their learning through Visual Thinking Strategies sessions:

This has helped me become more openminded as well as think more critically and deeply. I realize more than before that there is more than what is just above the surface.

Fostering Social Emotional Learning, in Adults, through VTS

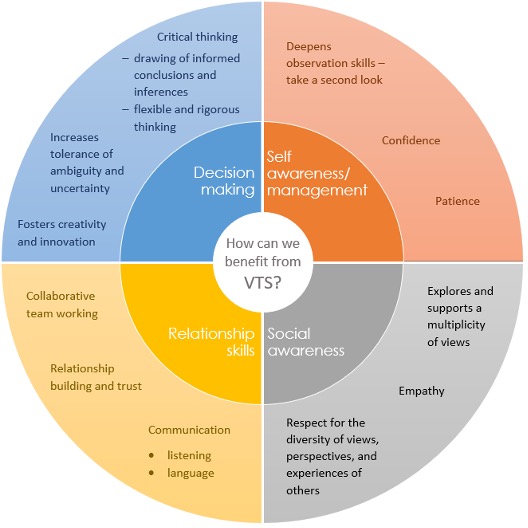

So much of providing meaningful healthcare, in our view, is about looking beyond first assumptions, employing a mindset of active inquiry and attuned exploration, and digging deeper to co-develop informed actions and/or solutions with patients and caregivers. This can be seen in action when a pharmacist explores the barriers to taking medicines with a patient and sometimes their family members. The group then generates and discusses ideas for overcoming those barriers together, rather than health professionals making hasty and unilateral decisions or assumptions. For these reasons, we find VTS supports a range of social emotional learning benefits—individual, collective, relational, and cognitive—that are highly valuable for adult learners in our health spaces. We have developed Image 1 to summarize and communicate several of the social emotional learning attributes and behaviors2 we have tried to foster in hospital pharmacy staff and undergraduate pharmacy students who have participated in regular VTS sessions.

Image 1 Reflections on ways in which VTS benefits social and emotional learning development of pharmacy health professionals

* The inner ring shows the theoretical social and emotional elements. The outer ring shows the practical skills and attitudes we believe are developed in VTS session attendees. The “we” in the center circle refers to the pharmacy profession.

Through regular VTS sessions, we have seen the development of elements of social awareness in our students in our university classes over the past seven years. We formally surveyed students who were part of our first two VTS pilot implementations of ten VTS sessions across year one of our pharmacy curriculum. Through this evaluation, one of our pharmacy students highlighted to us their personal “self-awareness” challenges as an emergent health professional:

One challenge is to overcome my bias and view things out of different viewpoints.

Another pharmacy student described the positive “social awareness” potentials they had experienced through their Visual Thinking Strategies sessions:

Benefits involve knowing that each patient comes in with a different history and cultural background. Thus, each will have elements that are more important to them than others as well as different interpretations for the same thing.

Reflecting on benefits gained through participation in our VTS sessions, a student further commented on their enhanced “decision-making.” They also discussed the personal challenges in transferring this type of academic learning to the real-world of pharmacy and healthcare:

… being able to be multi-dimensional and see things from all aspects is one of the biggest benefits of these sessions. It’s about acquiring the understanding that there is not one answer, just like in practice there are many ways to do it. I think the difficult part of this is actively thinking about it and implementing it into practice. I feel that after participating in these sessions, I am more able to accept diversity and think in other’s perspective. At the very beginning, I found that my interpretations were very definite.

Trudi facilitating a VTS session with pharmacy undergraduate year two students

Towards Development of “Multi-Dimensional” Mindsets

Collectively, we have learned that is not a foregone conclusion for all that VTS learning will transfer to the real world of healthcare delivery.3 It requires careful framing, reiteration, and constant purposeful attention (and yes, gentle persuasion sometimes too) in our hospital and undergraduate health settings. Perhaps surprisingly, this type of multi-dimensional disposition and thinking skillset can be novel in our health education and pharmacy settings.

For those unfamiliar with them, health and health education spaces are often constrained—by limited time, scarce resources, substantially demarcated roles and responsibilities, and tightly prescribed teaching curricula. In our VTS sessions with adults in health/education contexts, we have found a proportion of individuals with whom we work and learn expect to be presented with science or clinical content, or skills-building activities explicitly linked to professional practice. Initially, they are not expecting to be engaging with art in these VTS sessions, as they might be if they were visiting an art gallery or a museum. Additionally, the individuals who are often attracted to careers in health, in our case pharmacists and pharmacy technicians (pharmacist support staff), have experienced predominantly science-based education, which can involve a high degree of memorization of facts, formulae, checklists, and minute details of physiology and medications. In some cases, this learning approach produces individuals with overly binary or reductionist thinking.

This type of binary mindset and approach can be deeply at odds with today’s collaborative person-centered health practice approaches. Additionally, healthcare delivery requires individuals to work within an environment of complexity, sometimes with limited information, and often uncertainties about the best way forward for a patient. As a result, contemporary pharmacists and health professionals need the ability to adapt, to work holistically in teams to support nuanced decision-making within uncertain environments, and to show compassionate awareness of individuals’ health needs, beliefs, aspirations, and lived realities. In short, pharmacists need to provide health services and healthcare in a person-centered manner. All these aspects required are strongly embedded in the “relationship skills” section and other areas of the social emotional learning circle shown in Image 1 above. These are validated by feedback on complex social and emotional skills that pharmacy students report through participating in VTS learning. One student summarized their growth in developing empathetic, reflective support of patients’ needs through VTS sessions. They noted learning through Visual Thinking Strategies had supported them with being able to

… take into account the perspective and opinions of others, and to not just make decisions and conclusions based on my own understanding.

Providing person-centered care involves a pharmacist being a strong communicator and providing clear information to support self-care.4 It also requires the demonstration of empathy and respect, ensuring that individuals, and their support people such as family members, are involved in the decisions made about their health and medicines and that these decisions and preferences are respected by the pharmacist. We have found that education sessions using Visual Thinking Strategies provide numerous ideal opportunities for attendees to develop (or further develop) many of the transferrable personal, social, relational, and cognitive skills (shown in our Image 1 above) that are needed to provide this type of care to all. A pharmacy student reflected on developmental gains through VTS learning:

It has taught me that there is always more than one way to look at things and that different people might not always see everything in the same perspective. I was already aware of this but [VTS] made me recognize and think about it more often.

Humanistic Aspects of Hospital Collaborative Practice through VTS

Working in the hospital setting, Kim has explored implementing Visual Thinking Strategies within twelve continuing education sessions held at monthly intervals to lead pharmacy technician colleagues to discuss art as a springboard for deeper skills development. Pharmacy technicians support the work of pharmacists, and their training traditionally focuses more on undertaking tasks such as medicines supply rather than critical thinking. However, the roles of pharmacy technicians are expanding and increasingly require a broader skillset. The purpose of the sessions has been to increase development of critical thinking, communication, and teamwork, and the more humanistic aspects of practice within hospital pharmacy. The initial evaluation of the pilot group from 2016 showed trends to the development of critical thinking and transference of this to prescription review activities.

Kim has increasingly moved from using exclusively art images to also including discussion of medical prescriptions using the VTS method. The VTS questions work without significant change. Question 1 is adapted to “What’s going on in this script [prescription]?” Question 2 sometimes needs adapting to “What makes you say that?” when it is apparent that participants are drawing on clinical pharmacy knowledge exclusively, rather than on observation. In such cases, follow up with a more traditional form of Question 2 can assist participants in melding knowledge and observation and questioning their own assumptions. Some changes in the traditional VTS ground rules have been needed to reflect and acknowledge the narrower range of interpretations of right or wrong within a prescription (since there are clinically “correct” medications, doses, etc. required for patient safety). Kim has found it valuable to hold a general discussion after the end of the prescription “image” discussion to debrief any issues which emerged in the discussion that were not addressed fully. Or, where issues were not correctly interpreted from a safety perspective, to ensure that participants do not leave with misinformation. This in turn has led to the adult hospital pharmacy staff participants expressing an increased sense of relevance and purpose of the VTS education sessions. This understanding has been critical to the ongoing support for this non-traditional method in the hospital space, which is a constantly changing yet a highly resource-constrained setting.

Kim has also explored using VTS with groups of hospital staff of varying disciplines as a springboard for divergent thinking. She has used it at the start of hospital planning and staff development sessions to support enhanced observation skills development and empathy, and to foster creative thinking to generate more ideas in quality improvement teamwork discussions. In these sessions, Kim has found VTS to be a valuable tool to support collaborative critical thinking, in an environment drawing on content that is not linked to professional knowledge or roles. For this reason, Kim feels that VTS supports a safe, unbiased, level playing field, in which to develop these skills and to share collegial thinking. This is significant in the hospital setting that can often be very hierarchical with the voices of senior staff likely to be heard more than juniors. Using VTS as a springboard “space setter” at the beginning of team discussions and skills-building sessions seems to enable adults who are working in a dynamic health environment to tap into a more creative mindset and enhances their ability to think critically and collaboratively.

Pharmacy Undergraduates with Curious Minds Open to Different Possibilities through VTS

Similarly, in the highly constrained university pharmacy undergraduate curriculum, Trudi and Lynne have creatively prioritized ten 20–30 minute VTS sessions within existing classes that focus on communication and professional skills development for emerging pharmacy professionals. The dominant view of our students surveyed between 2016–2020 has been that the VTS method offers them personal and professional learning opportunities that they do not experience elsewhere at university. Many students report a shift in mindset from one that initially focused on seeking the “closed/defined” answer, to one that values curiosity and embraces openness to multiple possibilities, perspectives, and approaches. As one student described it, Visual Thinking Strategies sessions

… allowed me to integrate an open mind or a “no assumptions” mindset when approaching all types of scenarios.

In both our hospital and pharmacy education settings, by modelling and refining our collective practice, we have found VTS sessions can facilitate attunement to the social emotional side of learning, which in turn supports better collaborative group and teamwork. Through VTS we feel our students, and colleagues, learn to attend to the nuanced elements of communicating effectively within groups of diverse people—including the essential skill of knowing when, and how, to step back and actively listen. As one of our pharmacy students commented, their significant learning takeaway from VTS sessions was:

Listening to interpretation I disagree with and learning to stay quiet.

Overcoming Space, Time, and Resource Obstacles to Continue to Grow through VTS

In both our hospital and pharmacy undergraduate program spaces, there have been unique challenges in implementing VTS which originated with pre-university students in art galleries and museums. As a result, we have adapted the VTS process to accommodate a range of situational factors. VTS teaching for our staff and students is classroom based as we do not have easy access to museums or galleries and original artworks. This has meant finding suitable rooms with appropriate size, layout, and AV technology of sufficient quality and size to project large, good quality images. Kim has found that hospital staff needed to be physically together in a classroom setting and her attempts to move VTS online during COVID-19 have been less successful so far due to space and technology constraints in the workplace. Conversely, Lynne and Trudi have been successful in delivering VTS by Zoom to varied groups of students who are studying from home. They have found that students positively engage even in this online VTS mode, despite limitations in students’ personal environments, including technology glitches.

All three of us have found we have needed to adapt the VTS method for our largely adult participants in science-based health settings in the following ways:

- We have tweaked the ground rules, particularly for discussions using medical prescriptions, as described earlier.

- After the initial session, we do discuss with students why VTS is being used and what capabilities and dispositions we anticipate they will gain from participation.

- We sometimes provide guidance on what specific skills we would like them to focus on in the session, such as active listening or the use of sensitive vocabulary.

- We have chosen images with narrative relevance to our specific New Zealand context, and to a career in health. Example topics are diverse identities, colonization, and poverty.

- We have provided choice on the images used, from a limited curated selection around a particular topic. The first image used is always one chosen by Lynne or Trudi. After a few sessions, when students have become familiar with VTS, then students are asked to vote from three or four images, by raising their hand, to indicate which image they would like to use or indicate a ranking for each image using their fingers. The image receiving the highest number of votes/highest ranking is used. This has increased our adult learners’ motivation to engage. Kim has also adopted this approach with some groups of staff in hospital settings.

Working and teaching in a science-based environment has meant overcoming some challenges in getting buy-in and engagement from others at organizational and individual levels. There are colleagues who have not always understood the necessity or benefits of the social emotional learning focus of the method. Some have seen VTS sessions as less than essential, rather, as a “fluffy extra” in busy work and learning spaces still somewhat dominated by scientific knowledge/approaches.

Creating opportunities for others to experience VTS as participants themselves is a valuable tool to influence managers about the value of dedicating time and space for this for staff and students. We have had to be flexible, as training of this sort can still be viewed as a “nice to have” and can get deprioritized when workload or other priorities such as COVID-19 take over.

Summary Thoughts

Below are individual final summary thoughts from Trudi, Kim, and Lynne about their experiences and explorations in facilitating and learning through Visual Thinking Strategies.

Trudi

For me, facilitating a VTS session always creates excitement and a little anxiety. Despite their predictable rhythm, the possibility of alchemy from the unique combination of the image and participants, always exists.

I love how just when you think you have heard all the possible interpretations of an image, a group finds another, and you see the image afresh. VTS surfaces students’ hidden strengths and characteristics. The appreciation of these strengths by other group members helps to grow students’ confidence and builds group cohesion.

Kim

I am constantly amazed at the diversity of thinking and perspectives uncovered by VTS discussions in a way that daily conversations with colleagues do not.

I really enjoy seeing initial scepticism about VTS transformed into enthusiasm for more as they experience it for themselves.

I also appreciate the way VTS has deepened my facilitation skills and the transference into my everyday management practice.

Lynne

VTS continues to impress me as being a deceptively simple process with a vastly complex set of unique outcomes. I never tire sharing the potential for collaborative insight and inspiration as our students (and I) gain greater self-awareness and perceptiveness about the unique viewpoints within our group.

Seeing students take risks individually, and collectively, sparks me to keep striving to be brave as an educator and to keep stepping “outside the box” with them in all areas of our learning.

Through this, we remain committed to the value and benefits of Visual Thinking Strategies for us as clinical educators and for healthcare professionals. As a method we see it supporting a multiplicity of views; encouraging empathy and respect for views of others; increasing tolerance of ambiguity; and encouraging participants to draw informed conclusions and inferences. Our VTS practice as facilitators continues to require thoughtful, ongoing experimentation, and careful consideration and framing of the deeper purposes of VTS to our pharmacy students and hospital staff. It regularly involves us shining a light on the observed and reported benefits of VTS within our hospital and undergraduate settings to assure Visual Thinking Strategies remains in a central space for the social emotional learning development of our future pharmacy workforce.

Our research of our pilot project implementing VTS within our pharmacy undergraduate program was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee on 14th September 2017, reference 019176.