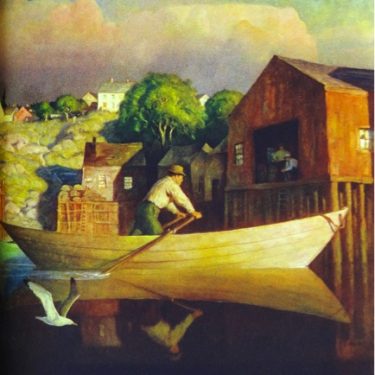

Mina: “These little children in the house, is trapped. Can’t go outside. Water is high.”

Safiya: “Beautiful house, tree, seagull.”

Habiba: “That’s pigeon?”

Mina: “No seagull, pigeon is smaller.”

Yena: “Boat in water.”

Sujan: “It is not now. Houses were made of wood. Boat is also from the past, yes.”

Mina: “Now in America same, houses of wood. People not rich, same houses. Man with hat. A cowboy.”

Mohamed: “America has cowboys.”

Tenzin: “In Holland there was flood. This man helps people.”

Safiya: “Maybe Dad comes home after a long time, maybe from work. Sometimes fishing one or two months on water. This is my thinking.”

Habiba: “No children. Maybe big people drinking tea, looking outside.”

Safiya: “I think no children either.”

Tenzin: “Sometimes I see these in other country. This man has groceries with food.

Mina: “Sujan, what do you think?”

Sujan: “I have finished.”

Original conversation in Dutch:

Mina: “Deze kleine kinderen in huis, is vast. Kan niet naar buiten. De water is hoog.”

Safiya: “Mooi huis, boom, meeuw.”

Habiba: “Dat is duif?”

Mina: “Nee meeuw, een duif is kleiner.”

Yena: “Een boot in het water.”

Sujan: “Het is nu niet. Vroeger was huis van hout. De boot is ook van vroeger ja.”

Mina: “Nu in Amerika zelfde, huis van hout. De mensen niet rijk, dezelfde huizen. Man met hoed. Een cowboy.”

Mohamed: “Amerika heeft cowboys.”

Tenzin: “In Nederland was een watervloed. Deze man helpt mensen.”

Safiya: “Misschien komt papa thuis na lange tijd, misschien van werk. Soms met vissen een of twee maanden op water. Dit is mijn denken.”

Habiba: “Geen kinderen. Misschien grote mensen thee drinken, kijken naar buiten.”

Safiya: “Ik denk ook geen kinderen.”

Tenzin: “Soms zie ik deze in ander land. Deze man heeft boodschappen met eten.”

Mina: “Sujan wat denk je?”

Sujan: “Ik ben klaar.”

We have begun. This is our first VTS discussion. We will be having a lot of VTS sessions these weeks. I am curious to see what the sessions will have in store for us. We will consider these weeks as a learning project: the students can experience VTS in practice; I will discover what VTS has to offer for our literacy lessons; and I will record the sessions and document the process.

About ten adult students participate in my literacy classes. Dutch lessons are part of the integration process in the Netherlands for refugees and people from outside the EU who are settling in the Netherlands for an extended period. We often work together for several years on oral and written language skills.1 My students come from countries including Nepal, China, Tibet, Morocco, Ethiopia, Syria, and Eritrea. Most came to the Netherlands as refugees. They all started in the group as either illiterate (with little ability to read or write in any language) or literate in a language that does not use the Latin alphabet. The length of time they have been at school in their country of origin differs. The average student went to school for a couple of years, but there is also a student who attended primary school and secondary school and someone who did not go to school at all. Some of them share a first or second language (Tigrinya or Arabic), and sometimes they translate words for each other.

Struggling with Functional Illiteracy

The students belong to the growing group of persons struggling with functional illiteracy. They are not able to read or write well enough to do things that are needed for living and working in present day, industrial society.2 According to the International Literacy Association,3 there are 750 million (functional) illiterate individuals worldwide and this group is growing.

In the Netherlands one in nine persons between the ages of 16 and 65 encounters similar challenges. Of this group, 65 percent has Dutch as their first language. In this article I will focus on second-language learners: my students.

The Benefits of VTS

VTS uses art to teach thinking, communication skills, and visual literacy, in the belief that growth is stimulated by looking at art of increasing complexity, responding to questions and participating in group discussions, according to Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine.4 Growth in visual literacy, the ability to read, write, and create visual images,5 can help students read more easily in a functional way. Many informational materials contain images and infographics that are easier to understand if you are visually savvy. After all, you have learned to read images better. What part of the image tells the message? Which details are relevant, and which are not? How should the entire image be interpreted?

Furthermore, research shows that special attention for visual reading has a significant positive effect on students’ overall language skills, including writing.6 This is unsurprising, because learning to read and write and learning to look are both visual processes. Making the links between sounds and characters involves a visual aspect. You will have to look carefully to learn to distinguish the different characters.

This also works in the other direction. Research in North India7 shows that people who learn to read become better at visually recognizing things, such as faces, people, and houses.

Choosing Meaningful Content

Other features of VTS also align well with effective second-language acquisition. Meaningful content is both crucial in VTS and in successful second-language acquisition. My students are more easily involved when images connect with their current perception of the world and when they are recognizable. VTS gives you the space to choose images that match students’ interests, so you can further increase their engagement. A large majority of my students in this group are parents. Talking about their family is important to them, so I often chose images with family scenes and children. This is consistent with Abigail Housen’s research and Theory of Aesthetic Development. Her descriptions of beginning art viewers informed a number of my choices.

I decided to start from scratch. None of my students had had any previous experience with VTS discussions. I also knew that they had not encountered many works of art during their stay in the Netherlands and they had not yet visited a museum. For these reasons, I decided to choose artworks that were appropriate for Accountive viewers, viewers in Stage I of Aesthetic Development, where the emphasis is on concrete and personal observation.8

Research shows that collaborative learning and interaction have positive effects on language acquisition.9 VTS is a method in which cooperation and talking together are central aspects. It is important for students to produce language freely and then notice their own mistakes or have a fellow student point them out constructively. For example, a student is saying, “A mother keeps a child.” (“Een moeder houdt een kind.”) A different student then uses the verb “to hold.” (“vasthouden.”) “The mother is holding a child.” (“De moeder houdt een kind vast.”) The others begin to reproduce the newly introduced word in the continuing conversation.

The students also increased their vocabulary, thanks to each other’s input. Often, they wanted to describe something in the image and asked, “What is this?” or “What is the word?” Then often one of the other students would come up with the word. In some cases, I could help them when I paraphrased their answers. In my teacher training for Dutch as a second language, I often heard: offer new words in a meaningful, logical context. Hearing and using new words during a VTS session—while looking at the artwork that evokes the new vocabulary—is certainly an example of a pregnant context.

Literacy Assignments

I followed each VTS discussion with a literacy assignment. Often, I asked the students to name the new words they had heard during the conversation and then to write sentences including the words. Sometimes we did a dictation or made a word web based on a key word. We tried to recall the new words in the next lesson. Which ones did we remember? Could we still write them? After the first discussion quoted above, the students wrote sentences.

NC Wyeth, The Doryman, Oil on canvas, National Museum of American Illustration

Yena: A man in the boat.

Tenzin: Nice wood house. I see a cowboy in the boat.

Habiba: I see house. I see a seagull. I see two people in house. I see the man. Finished.

Sujan: I see old wood house. I see tree. I see wood boat. I see clouds. I see two men in house. I see a man in a boat.

Mohamed: I see boat. I see water. I see tree. I see houses. I see seagull. I see balcony. I see three men.

Yena: Een man in de boot.

Tenzin: Mooi hout huis. Ik zie een cowboy in de boot.

Habiba: Ik zie huis. Ik zie een meeuw. Ik zie twee mensen in huis. Ik zie de man. Klaar.

Sujan: Ik zie oud hout huis. Ik zie boom. Ik zie hout boot. Ik zie wolken. Ik zie twee mannen in huis. Ik zie een man in boot.

Mohamed: Ik zie boot. Ik zie water. Ik zie boom. Ik zie huizen. Ik zie meeuw. Ik zie balkon. Ik zie drie man.

At this stage, the sentences were short. Students were not yet using conditional language and they rarely used adjectives.

Palmer Hayden, The Janitor Who Paints, c. 1937, Oil on canvas, 39 1/8 x 32 7/8 in, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Four discussions later we talked about the picture above. Students used more conditional language, their sentence structures were more complete, they explored many details, and made comparisons.

Me: “What more can we find?”

Safiya: “Finished, teacher. ”

Habiba: “No not finished. The man has a nice tie and shirt. The woman has nice shoes. The woman has beautiful flowers, earrings, hairstyle.”

Other students: “The child might be angry. The cat seems tired. The child has big eyes, just like Safiya. Maybe the woman’s coat is hanging on the coat rack. Is it a window or a picture? Maybe the woman has a baruka. What is that in Dutch? Oh yes, wig.”

Ik: “Wat kunnen we nog meer ontdekken?”

Safiya: “Klaar docent.”

Habiba: “Nee niet klaar. De man heeft een mooie stropdas en overhemd. De vrouw heeft mooie schoenen. De vrouw heeft mooie bloemen, mooie oorbellen, mooi kapsel.”

Andere cursisten: “Het kind is misschien boos. De poes lijkt moe. Het kind heeft grote ogen, net als Safiya. Misschien hangt de jas van de vrouw aan de kapstok. Is het een raam of een foto? Misschien heeft de vrouw een baruka. Wat is dat in het Nederlands? O ja, pruik.”

After the conversation, I asked the recurring question: “What are the new words?” The students immediately produced complete sentences, without thinking.

Habiba: “The man paints the lady.”

Sujan: “The cat is sleeping soundly.”

Habiba: “De man schildert de mevrouw.”

Sujan: “De kat slaapt lekker.”

They made grammatically correct statements and used more adjectives. They also searched actively for specific words, such as a word you would use for a little angry.

Sujan: “The child looks angry.”

Tenzin: “No not angry. My son looks like that sometimes. He doesn’t like it.”

Me: “Maybe cranky? That’s a little angry.”

Tenzin: “Yes, cranky.”

Sujan: “Het kind kijkt boos.”

Tenzin: “Nee niet boos. Mijn zoon kijkt soms zo. Hij vindt het niet leuk.”

Ik: “Misschien chagrijnig? Dat is een beetje boos.”

Tenzin: “Ja, chagrijnig.”

We also examined the words focus and winking.

Tenzin: “Teacher, how do you say? The man looks serious and works hard.”

Me: “You mean focused? Who knows what that is?”

Safiya: “When I talk in class, I have no focus. Maybe you get angry.”

Habiba: “Yes Mina and Safiya talk a lot. Like this: ‘bla bla bla’.”

Mina: “I never talk in class.” (Mina winks).

Me: “That’s a wink! Look – but I can’t do it very well.” (Everyone laughs).

Tenzin: “Docent, hoe zeg je dat? De man kijkt serieus en werkt hard.”

Ik: “Bedoel je geconcentreerd? Wie weet wat dat is?”

Safiya: “Als ik praat in de les, heb ik geen concentratie. Misschien word jij boos.”

Habiba: “Ja Mina en Safiya praten veel. Zo: ‘bla bla bla bla’.”

Mina: “Ik praat nooit in de les.” (Mina knipoogt).

Ik: “Dat is een knipoog! Kijk! Maar ik kan het niet goed.”

Reflecting and Reviewing

After eight VTS sessions I was curious about the students’ experiences. I asked several questions: “Do you like the lessons? Are they important for you? Do the lessons help you improve your Dutch (talking, listening, learning new words)? Do you learn and see new things?” Their appreciation of the lessons was great. Besides confirming that they enjoyed the lessons and that they learned new words, they also explained to me how the lessons enriched their lives. For example, when the focus was on a particular garment, other students could often add more about the possible material or origin of the garment. Where was it possibly worn, by whom, and in what time period? VTS gave them the opportunity to share information and experiences. They all loved hearing the interpretations and stories from their peers and learning from this.

I also took some time to reflect. Overall, I was satisfied with the discussions and could relate to the positive comments of the students. Prior to this experiment, I facilitated VTS discussions in groups with higher-level language learners. I could more easily guide students through the structures of a VTS discussion, such as taking a quiet moment to look, paraphrasing after a student had spoken, and conveying the meaning of the second question: What do you see that makes you say that? During the experiment, it took more time and effort to get used to the habits of a VTS discussion. Sometimes we spoke at the same time or the second question was difficult to understand. My strategy was to leave it as it is and then move on to the third question: What more can we find? But maybe in the future I will think of other ways to handle this, and also exchange ideas with colleagues who work with VTS.

Nik Wheeler, Children Playing on a Slide, Muscat, Oman, Color photograph

Windows and Mirrors

Apart from literacy benefits, I noticed again how much pleasure VTS discussions can give in the classroom. The discussions create a positive atmosphere. Students gather inspiration and new knowledge. We experience a lot of ambiguity in life and discover new perspectives when we look carefully at an artwork. I consciously looked for pictures that either connected to the cultural heritage of some of the students or, on the contrary, allowed new worlds to unfold. For example, when an image struck a chord with a student, I often saw the joy of recognition and I also thought I detected a sense of pride. The student in question was then able to pass on knowledge and the others absorbed this with curiosity. When we looked at Children Playing on a Slide by Nik Wheeler, all these associations with Arab countries came up. The picture transported some students back to countries such as Morocco and Syria, as they examined the similarities and differences between playgrounds and clothing from their youth and those in the picture. Another time in a different group we were looking at Sorting of the Cocoons, from a book on the Silk Industry, Qing Dynasty, early 19th century. A broad smile appeared on the face of a student who was originally from China. He made it clear to us with gestures and some Chinese and Dutch words that he recognized the silk cocoons in the picture.

The images worked as a window or mirror: seeing the reality of others through a window or seeing your own reality reflected in a mirror. Emily Style’s article “Curriculum As Window and Mirror” is inspirational for me.10 When someone’s identity is reflected (the image as a mirror), the image can positively influence pride and self-confidence, and affirm that student’s identity. They are not just the student who left their home country because of a devastating war. When fellow students and I experience an image as a so-called window, we can become a small part of someone else’s experience and imagery. We develop our empathy and mutual understanding by getting into contact with an inexhaustible diversity in social, cultural, and historical contexts.

Sorting of the Cocoons, From a book on the Silk Industry, China, Qing Dynasty, early 19th century, Bibliothèque Municipale, Poitiers, France

To conclude.

Student: “Nice picture teacher. But finished now. “

Cursist: “Mooie foto docent. Maar nu klaar.”

And then we shift our attention to the next part of the lesson.

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank all the students in my group from the school of languages Akros for contributing and giving permission to use their quotations. I also would like to thank Akros for their enthusiastic response when I announced the production of this article. The names of the students have been changed to respect their privacy.

Questions or comments? Contact us.

Footnotes

- 1 - “Integration in the Netherlands,” Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs, Accessed June 2022. https://www.inburgeren.nl/en/integration-in-the-netherlands/index.jsp

- 2 - Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus, Cambridge University Press, Accessed March 2022, “functional illiteracy.” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/functional-illiteracy

- 3 - “Why Literacy,” World Literacy Foundation, Accessed March 2022. https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/why-literacy/

- 4 - Abigail Housen, Philip Yenawine, updated by Madison Brookshire, Understanding the Basics (Visual Thinking Strategies, 2018).

- 5 - “What is Visual Literacy?” Visual Literacy Today (The Curved House). Accessed March 2022. https://visualliteracytoday.org/what-is-visual-literacy/

- 6 - Mustafa Kaya, “The Impact of Visual Literacy Awareness Education on Verbal and Writing Skills of Middle School Students,” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 8 (2020): 71.

- 7 - Michael Skeide, Uttam Kumar, Ramesh Mishra, Viveka Tripathi, Anupam Guleria, Jay Singh, Frank Eisner, Falk Huettig, “Learning to read alters cortico-subcortical cross-talk in the visual system of illiterates,” Science Advances 3 (2017).

- 8 - “Overview of Aesthetic Development”. Visual Thinking Strategies. Accessed March 2022. https://vtshome.org/aesthetic-development/

- 9 - Annela Teemant, Stefinee E. Pinnegar, “We Can Talk: Cooperative Learning in the Elementary ESL Classroom: Summary E,” Principles of Language Acquisition (EdTech Books, 2019), Accessed March 2022. https://edtechbooks.org/language_acquisition/cooperative_learning_elementary_esl_classroom

- 10 - Emily Style, “Curriculum As Window and Mirror,” Listening for All Voices (Oak Knoll School monograph, Summit, NJ, 1988), Accessed March 2022. https://nationalseedproject.org/Key-SEED-Texts/curriculum-as-window-and-mirror